By Liz Wagner

Since it disturbs the natural flow of reading, the fragment form constitutes one of the most striking literary features of contemporary migration narratives. Literary fragmentation always renders a sense of rupture, both as a physical break on the page, as well as a symbolic rupture that exteriorizes a character’s broken self. For each of Eden Robinson’s and Kim Thúy’s protagonists, this inner breaking has a different source. In Thúy’s Ru, An Tinh finds herself in a continual process of marrying her Canadian and Vietnamese identities while remembering her traumatic past as one of the boat people fleeing their homeland during the Vietnam War. Although Robinson’s “Dogs in Winter” is not formulated in a fragmentary mode, it shares Ru’s narrative jumps in time and place. Robinson’s short story offers a glimpse into the life of Lisa, a presumably Indigenous adolescent deeply affected by the criminal actions of her mother. Traumatic memories have a tremendous impact on the young protagonists, as they can actively blur the lines between the past and the present. Likewise, both characters grapple with the effect of sensory memories, which emerge passively and uncontrollably in their consciousnesses. While Ru’s protagonist An Tinh experiences trauma and abjection through physical migration and her experience as a refugee, Lisa interiorizes her trauma, expelling the abject from within. Through the ubiquity of memories, the emphasis on the sensory realm, and the recurrence of abject representations in each narrative, Eden Robinson and Kim Thúy craft stories whose detachments from temporal anchors generate highly disorientating ambiences wherein the characters are unable to belong. Abjection, as a desperate expression of rootlessness, functions as a means of demanding visibility, space, and voice in both Ru and “Dogs in Winter.”

In Thúy’s and Robinson’s respective works, memory brings the past into the present, whether consciously conjured, unexpectedly manifested, or knowingly ignored. In Ru, memory represents a manner of illustrating the horrors of war while offering a tool for the protagonist’s healing: the fragment form, or “bricolage.” As articulated by Claude Lévi-Strauss, the “bricolage” denotes the remains of a memory while also being constitutive of it (14). The end of each fragment already entails the beginning of the subsequent vignette and each memory fragment is built upon another. An Tinh recollects, for example, how her mother would recite a specific proverb, “Life is a struggle in which sorrow leads to defeat” (12). This proverb, learned in Saigon, informs the mother’s life in Canada: “[She] waged her first battles later, without sorrow. She went to work for the first time at the age of thirty-four” (13). The repetition of words from a similar lexical field, such as “sorrow,” “battle,” “struggle,” connects the mother’s distant past in Saigon to her present in Quebec: the lesson applies to both times and places. At the same time, this repetitive diction creates a distinct narrative flow that blurs and bridges these two temporalities, remaking them as one. This simultaneity of times reflects An Tinh’s fluid sense of identity, which is not linked to a spatial or temporal confinement, but is rather constructed through past and present as simultaneous realities.

As in Ru, “Dogs in Winter” offers bits and pieces of a memory, but in the latter work, the readers have to put together the information themselves. After Aunt Genna’s murder, Lisa remembers, for instance, “looking down at Mama’s shoes and seeing little red flecks sprayed across the tips like a splatter paint [she]’d done in kindergarten. [She] remember[s] Mama giving [her] a bad-tasting orange juice, and then [she] remember[s] nothing” (Robinson 54). Here, Lisa emphasizes details, such as the “the little red flecks” on her mother’s shoes. The sudden insertion of “and then [she] remember[s] nothing” at the end of the paragraph, visually set apart by a comma, suggests that the opposite is true. The girl has made an important connection between her mother’s sudden arrival, the banging noises on the upstairs floor followed by a dragging sound, and the sprinkles of blood on her mother’s shoes. Instead of facing the traumatic truth of this event, Lisa chooses to not remember, illustrating Martin A. Conway’s theory of memory. In his article “Recovered Memories and False Memories,” Conway examines memory as a moldable piece of dough, unfixed and malleable to the individual’s needs. Conway not only implies that memory can adopt human traits and is growing, developing, and ageing over time; he also suggests that a person has the option to reject a specific memory if its outcome is problematic or could compromise the subject’s mental health—which is what Lisa chooses to do in this particular moment. As for An Tinh, she actively decides to remember one of the Monsieur An’s mental crises: “And bang, he was spread out on his back. BANG! He cried out ‘BANG!’ several times, then burst out laughing” (Thúy 85). Instead of sharing how this violent experience has shaped her, An Tinh resorts to demonstrating his impact on her only through the narrative space she allots him, all the while telling Monsieur An’s story across three fragments, a story that has yet to be told. Ru tells the other side of the story, Vietnam’s, and humanizes Monsieur An rather than labelling him as mentally ill.

In later scenes grappling with sex work and child abuse, An Tinh’s voice remains equally poised, and her prose adopts an almost lyrical quality. The use of poetic language when addressing traumatic and violent encounters generates a contradiction between form and content, which reflects and highlights the disturbing nature of these incidents. While in Vietnam, An Tinh converses, for instance, with individuals who frequent sex workers. Rather than openly expressing her own thoughts and concerns about sex work and those who take advantage of it, the protagonist chooses to diverge into the realm of poetic language and its workings. She offers narrative space to discussions of Vietnamese and English accents and mispronunciations, and concludes eloquently: “a single accent for a single moment of happiness” (Thúy 123). Here, the “accent” is a metonymy for the sex worker, while the “moment of happiness” refers back to sexual intercourse. Moreover, the poetic quality of this sentence is underscored through its parallel structure. This parallelism ultimately presents sex workers, the “accents,” and their mirror functions of causing “happiness” as one grammatical entity. Through such lyrical and succinct elucidation, An Tinh renders the customers’ reduction of the sex worker to a mere “accent,” while the use of artistic language enables her to distance herself from such dehumanization.

In both “Dogs in Winter” and Ru, the senses are turned into effective memory carriers that allow for unmediated and unprepared movement into the past. Exploring the relation between memory and the senses, C. Nadia Seremetakis states that “the senses are meaning-generating apparatuses that operate beyond consciousness or intention” (6). Seremetakis further establishes a direct link between memory and the senses, explaining that a sensory memory transforms the past into a present reality (7). In other words, sensory memories are triggered by the stimulation of a specific sense; as sensory memories emerge uncontrollably, they are particularly impactful.In Ru, the protagonist reports, for instance, that she “discovered [her] own anchor when [she] went to meet Guillaume at Hanoi airport. The scent of Bounce fabric softener on his T-Shirt made [her] cry. For two weeks [she] slept with a piece of Guillaume’s clothing on [her] pillow” (Thúy 110). In this example, the unexpected smell of fabric softener endows the protagonist with a feeling of being rooted, of being home. Home, then, is not linked to a smell, but rather to a stirred emotion.

Critics have invited readers to imagine memory as malleable, rather than immutable. Referring to the classical conception that memory is fixed in place and time, and therefore “constitutes an important anchor for memory as a remembered or fabricated origin or an origin made ‘real’ by matters of faith and custom,” Julia Creet invites readers to analyze memory not through its stasis, but rather through its shifting nature (7). Memory is no longer limited to one space or one definition; it travels and becomes portable, it is a “constant constantly on the move” (Creet 6). In the article “Flower Girl,” Mona Lindqvist specifically investigates memory in motion by looking at the relation between the sensory realm, memory, and trauma in childhood. According to her analysis, the sensory realm is heavily contributing to the construction of traumatic memories. Remembering traumatic events manifests itself through episodic, contingent and highly sensory recollection rather than through chronology, coherence and objectivity. The senses’ impact in memory creation strengthens the recollection of some episodes while numbing the vivacity of other traumatic instances (Lidqvist 186-7).

In “Dogs in Winter,” the protagonist’s memory is founded on such sensory connections. For instance, when Lisa attends a dinner at her friend’s house, the smell of the meal she is served triggers a traumatic memory, and this recollection projects Lisa immediately back into the past:

As she lifted the lid, the sweet, familiar smell of venison filled the room. I stared at my plate after she placed it in front of me.“Use the fork on the outside, dear,” Amanda’s mother said helpfully.

But I was down by the lake. Mama was so proud of me.“Now you’re a woman,” she said. She handed me the heart after she wiped the blood onto my cheeks with her knife. I held it, not knowing what to do. It was warm as a kitten.

“I think you’d better eat something,” Amanda said.

“Maybe we should take that glass, dear.”

The water in the lake was cool and dark and flat as glass.

[…]

Then I sprayed sour red wine across the crisp handwoven tablecloth that had been handed down to Amanda’s mother from her mother and her mother’s mother before that. (Robinson 60-1)

In this passage, “the sweet, familiar smell of venison” conjures a memory of Lisa and her mother killing a deer in the forest. Lisa’s mind instantly travels back in time and space to “the lake,” and remains completely detached from her physical existence. Moreover, the structure and verb tense of this scene a complement the sense of immediacy on a formal level: Lisa’s memory is so forceful that it breaks up the linearity of the narrative, and this rupture gives the impression that past and present occur simultaneously. Instead of using the past perfect to render the anteriority of the past, the text relies on the past simple to express Lisa’s present as well as her episodic memories; in doing so, the temporal simultaneity of Lisa’s coinciding realities dissolves the lines between past and present. This simultaneity becomes even more striking as both instances are narrated in the past tense while the reference to a memory would require the use of the past perfect so to render its anteriority. When the friend’s mother refers to the glass she ought to be using, Lisa still picks up on the word “glass” and includes imagery of glass in her description of the lake: “The water in the lake was cool and dark and flat as glass.” This very sentence, however, creates another layer of repetition and circularity in the short story, as it appears at the narrative’s beginning when Mama takes Lisa hunting (Robinson 41). Without the repetition of this sentence, the reader would not be able to make the spatio-temporal connection that allows for this putting-together of different elements of a single memory. Ultimately, the repetitive structure of this passage functions to mirror the disorientation Lisa experiences on a textual level.

Likewise, Lisa’s vomit, the “sprayed sour red wine,” recalls the splashes of Aunt Genna’s blood on Mama’s shoes. In both cases, the verb “to spray” refers to the abject—the blood and vomit; its recurrence, therefore, establishes a direct link between the red blood and the red wine. In his discussion of abjection, Michael Humphrey explains that the abject “is an internal bodily experience of fear, horror and pain in which the very self is brutally confronted and threatened with the reality of its own extinction of the ‘Self’ in the face of the ‘Other’” (2). In fact, the unclear separation of these two parts of identity is also reflected in the story’s depictions of Lisa’s cultural heritage: in spite of the presence of Indigenous imagery, such as hunting, there are no direct indicators that Lisa is, in fact, Indigenous. Cynthia Sugars explains that this lack of clarification is intentional on Robinson’s part because it enables a “dislocation of conventional constructs of identity and abjection” (1).

While the vomit expresses Lisa’s disgust and rejection of Mama, she can also only express this rejection by imitating her mother, by similarly causing a “spray” (Robinson 61). In the example above, Lisa unconsciously imitates her mother; the red wine she expels from her body mirrors the red blood that Mama sprayed onto her shoes. Fittingly, Cynthia Sugars posits that Lisa is afraid of becoming her mother, which is why she echoes “the early colonizers’ notion that savagery was ‘in the blood’” (4). According to this premise, her mother’s blood is an innate part of Lisa; to rid herself of this part of her identity, she is bound to expel it. Later, Lisa experiences a similar sensory memory, which is again linked to the abject in relation to her mother: when she looks at a painting of a peasant woman working in a field with a scythe, her stance reminds Lisa of her mother’s posture when she killed Ginger, the dog (Robinson 48). All the while communicating Lisa’s aversion towards her mother, memories of the abject as incarnated through the mother figure simultaneously tie an unbreakable knot between Robinson’s protagonist and her past. The more the girl contemplates her mother’s aggressive nature, the more she sees it in herself. Therefore, Lisa judges her fate to become like her own mother as sealed.

While Lisa believes that the abject lies within herself, Ru’s abjection stems from a negative association with a war-ravaged country and history, and mirrors the protagonist’s desire to expel this past. Nevertheless, Thúy’s narrative obtains its traumatic, abject quality through its descriptions of the world surrounding its child protagonist. For Jenny James, the presence of abject imagery with regard to the body directly results from the refugee experience in Ru (49). In the process of migration, the refugee has to endure “various erasures and dismemberings,” including both the physical dismembering of the body and the shattering of families (James 49). Ru draws particular attention to the abject when An Tinh flees from Vietnam and finds herself on boats and in refugee camps. In an early entry, she describes how she “walked directly on the clay soil where maggots had been crawling a week before. (…) They crawled up to our feet, all to the same rhythm, transforming the red clay soil into an undulating white carpet” (Thúy 27). Here, the protagonist meticulously depicts how the maggots move and appear to the Western reader, for whom this book is primarily intended, this description of maggots triggers a deep sense of revulsion. Maggots feed on dead animals, corpses, and rotting food. It is difficult for a reader to be compelled by this abject representation; yet that which repels also attracts (Livingston 288). The ubiquity of abject imagery in both Thúy’s and Robinson’s respective works account for the significance of the abject for the creation of trauma and memory.

In the accompanying fragment, An Tinh addresses at length the flies that whirred above “a gigantic pit filled to the brim with excrement, in the blazing sun of Malaysia” (Thúy 26). The word “blazing,” contrasts the revolting nature of feces with a sublime description of the sun. The protagonist adorns this fecal description by recalling how one of her slippers once “fell into the cesspit without sinking, floating there like a boat cast adrift,” implying that the excrement is too dense for the slipper to sink (Thúy 26). Through including excrement imagery into her narrative, which recalls emotions of fear and revulsion, Thúy’s protagonist deploys the prime function of the abject: the abrupt construction of a long-lasting, complex and multisensory memories. Likewise, An Tinh characterizes the boat, another element of the abject in the novel, as “a hundred-faced monster who sawed off our legs” at night, in an earlier entry (Thúy 5). Again, the abject nature of the monster and its implied violence underscore the potency linked to abject and sensory recollections. Furthermore, the use of metaphor in these instances generates another a disconnect between content and form, which, as in Thúy’s representation of trauma itself, amplifies the abject component of these renderings. Although these abject representations are intentional, and present the reader with what is perceived as obscene, horrific, and inappropriate, they function to draw attention to these stories: abjection enables the protagonists not only to tell their own stories and to be heard, but also to tell the stories of those with similar experiences.

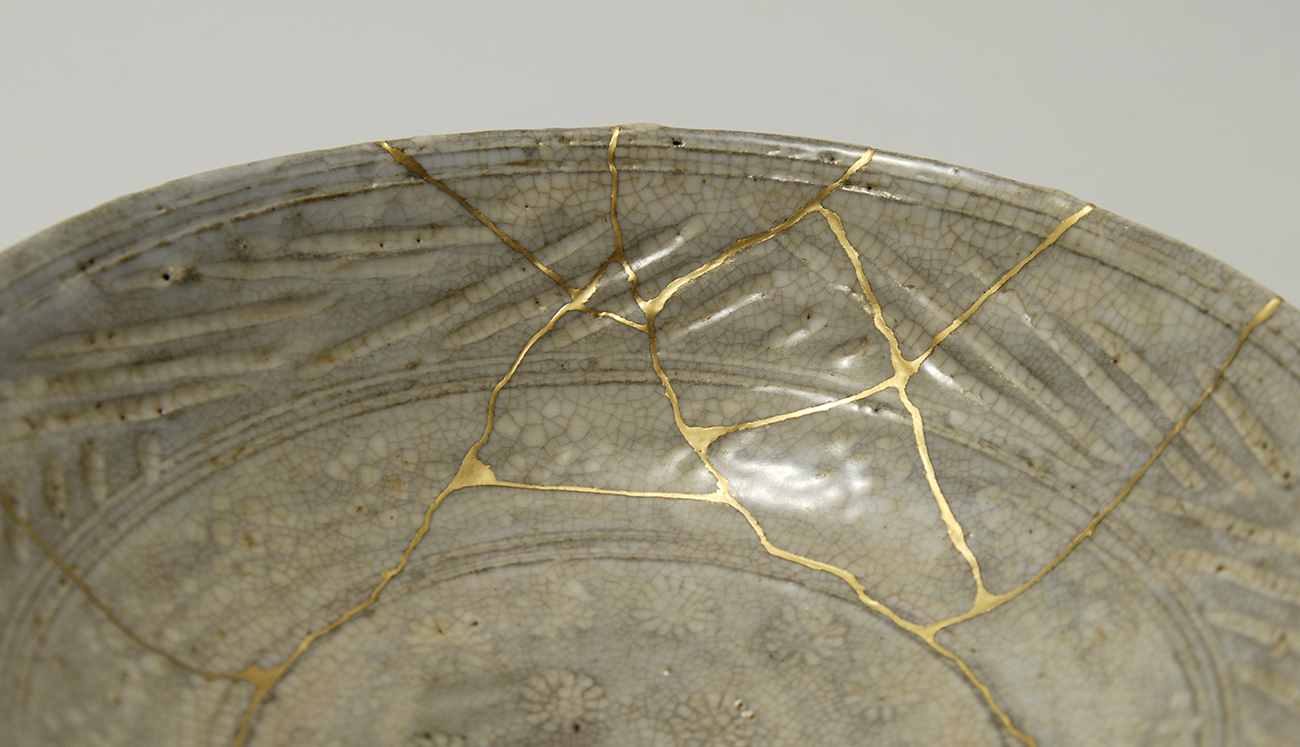

In Kim Thúy’s Ru and Eden Robinson’s “Dogs in Winter,” the protagonists deal with how to construct a self and identity, when faced with immediate dangers, such as war, or abusive and violent relatives. Their memories, no matter how disturbing, tell the stories of those who are often left in the margins. In these stories, abjection foists itself onto the readers, and forces them to read on: disgust can become more compelling than repulsive. For both of these characters, the colour blue is associated with the generational inheritance of trauma and memory. An Tinh is marked with this “blue spot on [her] backside, like the Inuit, like [An Tinh’s] sons, like all those with Asian blood” (Thúy 136). But for Lisa, the mongoloid spot has taken the shape of her mother’s turquoise dress – a colour which similarly calls upon visceral stirrings of memory amid abjection. Raised in a supportive system, Ru’s An Tinh is eventually able to close her wounds, to let them scar. Nevertheless, her scars will remain a constant reminder of her disruptive past. Kim Thúy and Eden Robinson illustrate this inherent rupture through its fragments, which, although connected like interwoven tissues, will never be the same as before – no matter how well the pages are tended.

Works Cited

Conway, Martin A. Recovered Memories and False Memories.Oxford University Press, 1997.

Creet, Julia. “Introduction: The Migration of Memory and Memories of Migration.” In .Memory and Migration: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Memory Studies. Edited by Creet, Julia and Andreas Kitzmann. University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Humphrey, Michael. The Politics of Atrocity and Reconciliation: From Terror to Trauma. Taylor & Francis, 2005.

James, Jenny M. “Frayed Ends: Refugee Memory and Bricolage Practices of Repair in Dionne Brand’s What We All Long for and Kim Thúy’s Ru.” In Melus: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the U.S. 41.3, 2016.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. The Savage Mind. Translated by George Weidenfield and Nicholson Ltd. University of Chicago Press, 1966.

Lindqvist, Mona. “The Flower Girl: A Case Study in Sense Memory.” In Memory and Migration: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Memory Studies. Edited by Creet, Julia, and Andreas Kitzmann. University of Toronto Press, 2014

Livingston, Julie. “Disgust, Bodily Aesthetics and the Ethic of Being Human in Botswana.” In Africa: The Journal of the International African Institute. Vol. 78 (2), 2008. 288-307.

Robinson, Eden. “Dogs in Winter.” In Traplines. Metropolitan Books, 1996.

—. Son of a Trickster. Alfred A. Knopf Canada, 2016.

Seremetakis, C. Nadia. The Senses Still. University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Sugars, Cynthia. “Sugars, Cynthia. “Strategic Abjection: Windigo Psychosis and the ‘postindian’ Subject in Eden Robinson’s ‘Dogs in Winter.'” In Canadian Literature, no. 81, University of British Columbia, 2004.

Thúy, Kim. Ru. Translated by Sheila Fischman. Vintage Canada, 2012

—. Mãn. Translated by Sheila Fischman. Vintage Canada, 2015.

Photo: “Chawan,” Makoto Watanabe