By Amelia McCluskey

Who is Nicole? The protagonist of Stéphane Lafleur’s Tu Dors Nicole (2014) is uncertain about her identity, lacking purpose as she drifts between vocations. During a summer in her early twenties, Nicole struggles with her lack of maturity and direction, seeking a sense of greater fulfillment. Along these lines, one can read Tu Dors Nicole as a bildungsroman, or coming-of-age film. While the bildungsroman narrative typically requires its protagonist to undergo a form of transformation, this active role is complicated when applied to a female hero on screen. In her seminal essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Laura Mulvey argues that the visual representation of women in narrative film is usually disempowering and eroticized, turning women into static objects of spectacle. Mulvey suggests that to refuse this voyeuristic pleasure, alternative forms of cinematic representation are necessary (816). To depict Nicole as the active subject of a bildungsroman narrative rather than a passive object, Tu Dors Nicole subverts traditional cinematic voyeurism, instead representing Nicole as a female voyeur. Rather than looking with an erotic gaze, Nicole’s observation of others allows her to gain information about the world around her, determining the kind of person she would like to become. Through her observation of her adult neighbours and her friend Véronique, Nicole is able to understand her own goals and emerging adult identity. I argue that Nicole’s role as a voyeur enables her personal transformation, allowing her to define herself in relation to her community while reclaiming the cinematic gaze. I will elucidate this argument by analyzing how the cinematography of Tu Dors Nicole allows Nicole to evade objectification, and how the voyeuristic scenes visually reflect Nicole’s perspective on her own identity, ultimately illustrating her internal character growth.

In literature, the bildungsroman was initially a male-dominated genre, following a young man’s entrance into society. Rita Felski observes that although female heroes have increasingly been represented in bildungsroman narratives, they have different traits than their male counterparts. Felski notes how—especially in the “money, sex, and power” narratives she describes—significant emphasis is placed on the woman’s glamour and beauty, which mitigates readers’ potential anxieties about her “masculinization” (110). This reassures readers that the woman can achieve growth and obtain forms of traditionally “male economic success” while preserving her “female (hetero)sexual” role (Felski 110). While literary bildungsroman texts draw attention to women’s glamour, Laura Mulvey highlights how in film, the presence of a woman on screen is already an “element of spectacle” and her erotic “visual presence tends to work against the development of a flow of action” (809). This suggests that placing visual emphasis on the spectacle of a woman’s glamour can instead diminish her role as an active agent in a film.

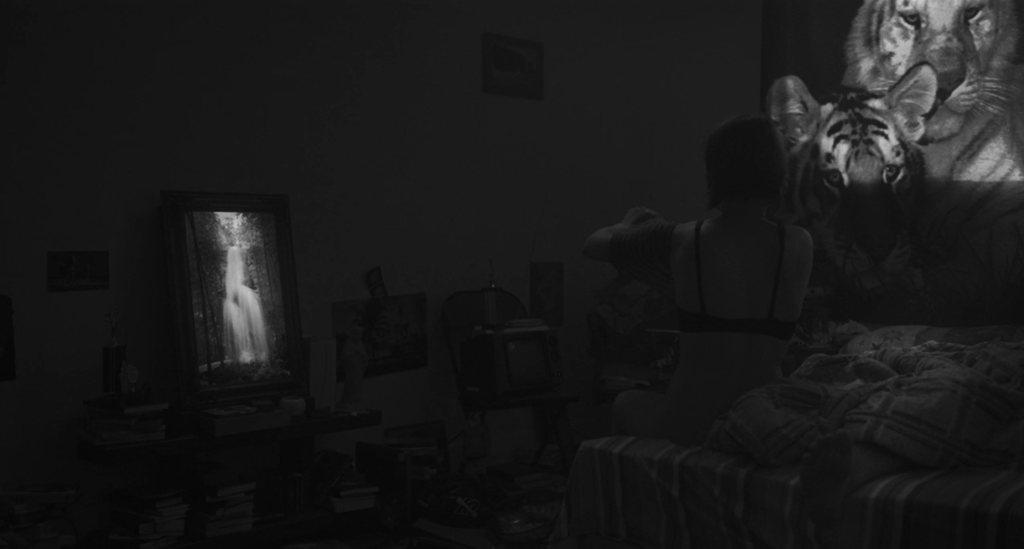

As a bildungsroman, Tu Dors Nicole’s cinematography employs subtle distancing effects to resist viewing Nicole through this erotic gaze, allowing her to appear as the active protagonist of her narrative. In the film’s opening scene, Nicole lies naked in bed with an unnamed lover, eventually leaving because she cannot sleep (Tu Dors Nicole 1:00-2:58). Despite her nudity, the framing of the shot detracts from a possible sense of eroticism. As she puts on a bra with her back to the camera, she is positioned on the far right side of the screen, sitting on the bed (see fig. 1). Scholar Marilyn Fabe notes that in film, women’s bodies “tend to be seen in pieces, [with] the camera focusing in on close-ups of body parts” while men’s bodies are “more likely to be seen in medium or full shots” (213). Here, however, Nicole is framed in a medium-full shot for an extended duration, depicting her with more neutrality than a series of close-ups would, as the viewers’ eyes are not directed to any specific “pieces” of her body. The surreal image of the waterfall in the mirror beside Nicole further detracts from her body in the shot. While Nicole sits hidden among the shadows, the mirror produces light, glowing on the opposite side of the frame to compete for the viewer’s attention. Its positioning on the far left creates a visual tension between the two subjects, causing the eye to constantly move back and forth across the frame. The mirror’s mysterious presence—along with its sounds of diegetic running water and tropical birds—receives no explanation, allowing it to remain a constant source of interest for the viewer.

Fig. 1. Nicole sits with her back to the camera. Tu Dors Nicole, Stéphane Lafleur, 2014.

The choice to film Tu Dors Nicole entirely in black and white further reduces Nicole’s potential as a visual spectacle, causing her to blend in with her surroundings. These effects repeat throughout the film, as Lafleur positions Nicole on the far edges of the frame or in long shots from a distance, evading the potentially objectifying gaze of the camera to allow her more freedom as a character.

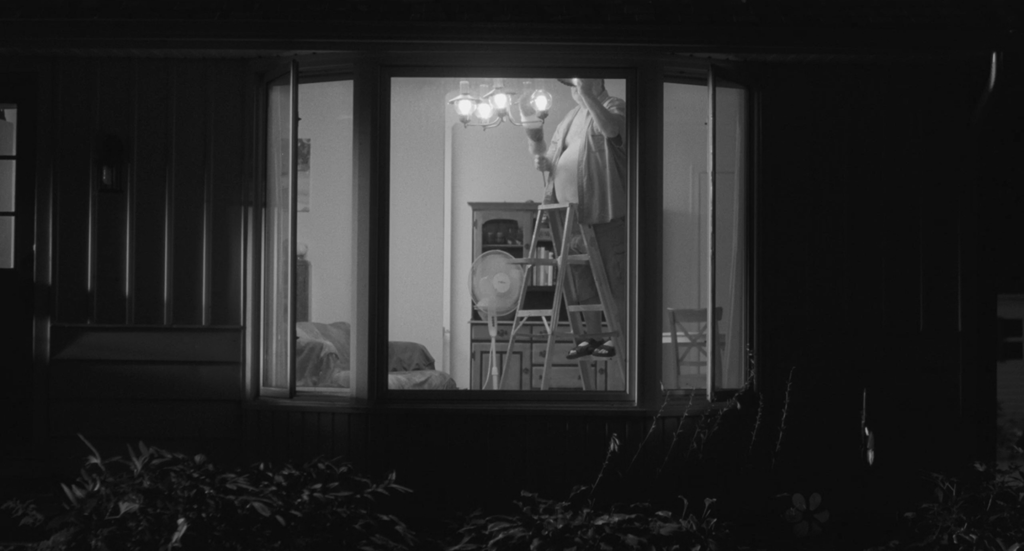

In deflecting this objectifying gaze, Lafleur instead depicts Nicole as the voyeuristic observer, looking through her neighbours’ windows and witnessing images of adult life. In Marilyn Fabe’s analysis of I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing (1987), she investigates how the film similarly reinterprets cinematic voyeurism. Fabe describes protagonist Polly’s voyeurism as not the “controlling, objectifying” gaze of a male voyeur, but a curious gaze, like “a young child who wants to know what adults do together when they are alone” (224). Moving beyond Polly’s innocent curiosity, an analysis of Nicole’s gaze reveals how it works as a tool to actively fashion her identity. Nicole’s reaction to the older adults in her neighbourhood reflects her ambivalence about the mundane claustrophobia of suburban life. In one scene, Nicole observes a woman on her porch in the early morning, letting her dog into the front yard (14:49-15:50). The woman stands starkly naked in a robe as she vacuums the dog’s feces off the lawn, which—paired with the dog’s repeated, panicked barks and jingling collar—conveys a sense of exaggeratedly intimate discomfort. Watching through her window, Nicole reacts to the woman with a mixture of amusement and disgust. Later, while standing in the street at night, Nicole watches an older man through his window as he stands on a ladder, dusting an overhead lamp (32:12-32:27). The man’s shirt is unbuttoned, exposing his stomach, and his face is partially obscured, indicating that he is unaware of being watched (see fig. 2). By displaying the man through a window surrounded by darkness, Lafleur creates an illuminated frame within the frame, imbuing the shot with an almost theatrical quality.

Fig. 2. The older neighbour through the window. Tu Dors Nicole, Stéphane Lafleur, 2014.

While these images of adulthood become a spectacle through their heightened intimacy, the spectacle only serves to emphasize their mundanity. Immediately following this shot, Nicole is pictured standing alone on a playground at night, reaching for the monkey bars (32:28). By juxtaposing Nicole’s voyeurism with a shot of her standing in a playground, Lafleur indicates Nicole’s growing ambivalence toward adulthood, seeing herself as not yet ready for its stifling responsibilities. Here, voyeurism is used not to articulate her erotic desire, but to indicate her distaste for her neighbours’ simple ways of life, engaging in domestic tasks in their suburban homes.

By contrast, the visual representation of Nicole’s best friend Véronique highlights Nicole’s desire for a different life than her own. Although she is uncertain about the responsibilities of adulthood, the film’s cinematography reflects how she craves Véronique’s sense of maturity. Unlike Nicole, Véronique possesses a car, an apartment, and a stable job. These symbols of adulthood allow JT, the object of Nicole’s affection, to see Véronique as an adult, while he only sees Nicole as his friend’s “little sis” (1:01:05). Through the film’s visual language, Lafleur displays Nicole’s desire for these greater freedoms. Early in the film, Nicole stares at Véronique while they sleep in the same bedroom (14:16). Véronique is unaware that she is being watched, yet the camera lingers on her for a duration of over 20 seconds as she lies asleep. This conveys a form of pleasurable looking—or what Mulvey defines as “scopophilia” (806)—as Nicole watches Véronique without her gaze being returned. Through this “lawless looking” (Fabe 211), Lafleur indicates Nicole’s desire for a different life. While Nicole is frequently portrayed in long shots that depict her body neutrally, this shot mimics the objectifying visual language that Mulvey and Fabe describe. By partially obscuring Véronique with a blanket, her body only appears in pieces—a bare leg, a shoulder, and a hand. As Nicole is not romantically connected to Véronique in the narrative, this subtle objectification visually illustrates her desire for the material pieces of Véronique’s life, which would grant her greater independence. Similarly, in a sequence by the pool (see fig. 3), Nicole watches, unobserved, as Véronique emerges from the water (43:17-43:39).

Fig. 3. Veronique emerges from the swimming pool. Tu Dors Nicole, Stéphane Lafleur, 2014.

By using high-key lighting and positioning Véronique in the centre of the frame in a revealing swimsuit, this shot visually emphasizes her physicality and confidence. In cushioning this image between shots of Nicole watching her from the side, the film subverts the traditionally male voyeuristic gaze by portraying the sexualized female body through the eyes of another woman. After observing Véronique, Nicole realizes that JT also admires her, confirming the reality of Véronique’s maturity. Rather than existing as merely erotic images, these shots illustrate Nicole’s envy of Véronique’s maturity and attractiveness.

This admiration of Véronique eventually turns into a disillusioned gaze, motivating Nicole’s character growth in the film’s conclusion. In the final scene, Nicole enters her parents’ bedroom and sees Véronique and JT lying in bed together (1:28:18-1:28:52). Rather than immediately framing the couple in bed when she opens the door, the editing of this scene removes any sense of voyeuristic pleasure, as the camera instead rests on Nicole’s reaction in the doorway. The image of the couple is only shown after Nicole leaves the room and violently pulls apart JT’s drum set, with the diegetic sound of the drums clattering in the soundtrack. This contrast between the cacophonous sound and their peaceful faces highlights the discontinuity between Nicole’s desires and her present reality. Seeing Véronique with JT allows Nicole to recognize her naivety in desiring him, bringing her to the realization that she does not need him. In the film’s final shot, the swimming pool erupts as a geyser in a moment of magical realism. The eruption works as a cathartic representation of Nicole’s internal growth, as she is pushed to reframe her priorities, moving out of stasis and into explosive action. While the traditional bildungsroman usually depicts a character’s growth through material changes in their life, here Nicole’s growth is symbolically represented through a change in the film’s visual language, with the geyser breaking out of the flat horizontality of the suburbs. This surreal representation of Nicole’s subjective point of view is facilitated through the depiction of her gaze throughout the film, as viewers are already aligned with her perspective. Here, Nicole’s appropriation of the voyeuristic gaze is ultimately what enables her growth.

As a bildungsroman narrative, Tu Dors Nicole foregrounds Nicole’s internal transformation and growing sense of maturity as she struggles to make sense of her adult identity. Nicole’s transformation is conveyed through her voyeuristic gaze, helping her introspect and understand her own desires. While films often portray women as passive sources of visual spectacle, Lafleur’s use of cinematography detracts from Nicole’s eroticization throughout the film, which allows her to function as an active protagonist. Tu Dors Nicole does not abandon voyeurism altogether, but instead uses it as a tool for Nicole’s identity formation, subverting the traditional male gaze. This film exemplifies how the female gaze operates in cinema as a whole, allowing a character to define herself in relation to others and resist objectification. Observing her older neighbours reveals Nicole’s disinterest in adult responsibilities, while watching her friend Véronique conveys her desire to be seen as more mature. Ultimately, Nicole’s gaze reveals the liminality of young adulthood, as she can no longer enjoy the comforts of being a child, but does not yet have a clear sense of her adult direction. Instead, Nicole can only wonder about her plans for the future, looking through windows into another life.

Works Cited

Fabe, Marilyn. “Feminism and Film Form: Patricia Rozema’s I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing.” Closely Watched Films, University of California Press, 2014, pp. 207-227.

Felski, Rita. “Judith Krantz, Author of the Cultural Logics of Late Capitalism.” Doing Time: Feminist Theory and Postmodern Culture, New York University Press, 2000, 99-115.

I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing. Directed by Patricia Rozema, Miramax, 1987.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, 1975, pp. 6-18.Tu Dors Nicole. Directed by Stéphane Lafleur, Microscope, 2014.