By Victoria Ranaudo

Joshua Whitehead’s Jonny Appleseed, explores the ramifications of Canada’s colonial past on Indigenous communities in the present through a queer lens. Despite its pursuit of independence and departure from the British Empire, Canada’s treatment of Indigenous groups as colonial subjects reproduces the same past it attempts to walk away from and asserts that there is no true end to colonialism in the country’s social infrastructure. Sara Ahmed proposes that the root of this phenomenon is found in Canada’s tendency to speak through the voice of the nation as opposed to the individual. She argues in her article “Affective Economies” that “The role of emotions is crucial to the delineation of the bodies of individual subjects and the body of the nation” (Ahmed 117). Taking her argument into account, Whitehead presents raw emotions through visceral imagery of bodily fluids being expelled from the body. In doing so, Whitehead proposes a method of breaking free from the reins of colonialism through an embracing of identity that threatens to seep outside of the body’s borders. Whitehead transposes his experiences of being a marginalized Oji-Cree and queer body onto his protagonist, and represents those pieces of his identity with the motif of the bear that follows Jonny throughout his journey. Additionally, Whitehead uses Julia Kristeva’s theory of abjection as a lens to regard how the excretion of bodily fluids from the body such as semen and sweat imitate the process of breaking free from the reigns of colonialism and repression. In doing so, Whitehead lays a roadmap for what constitutes the whole of Jonny’s existence, down to the smallest atom.

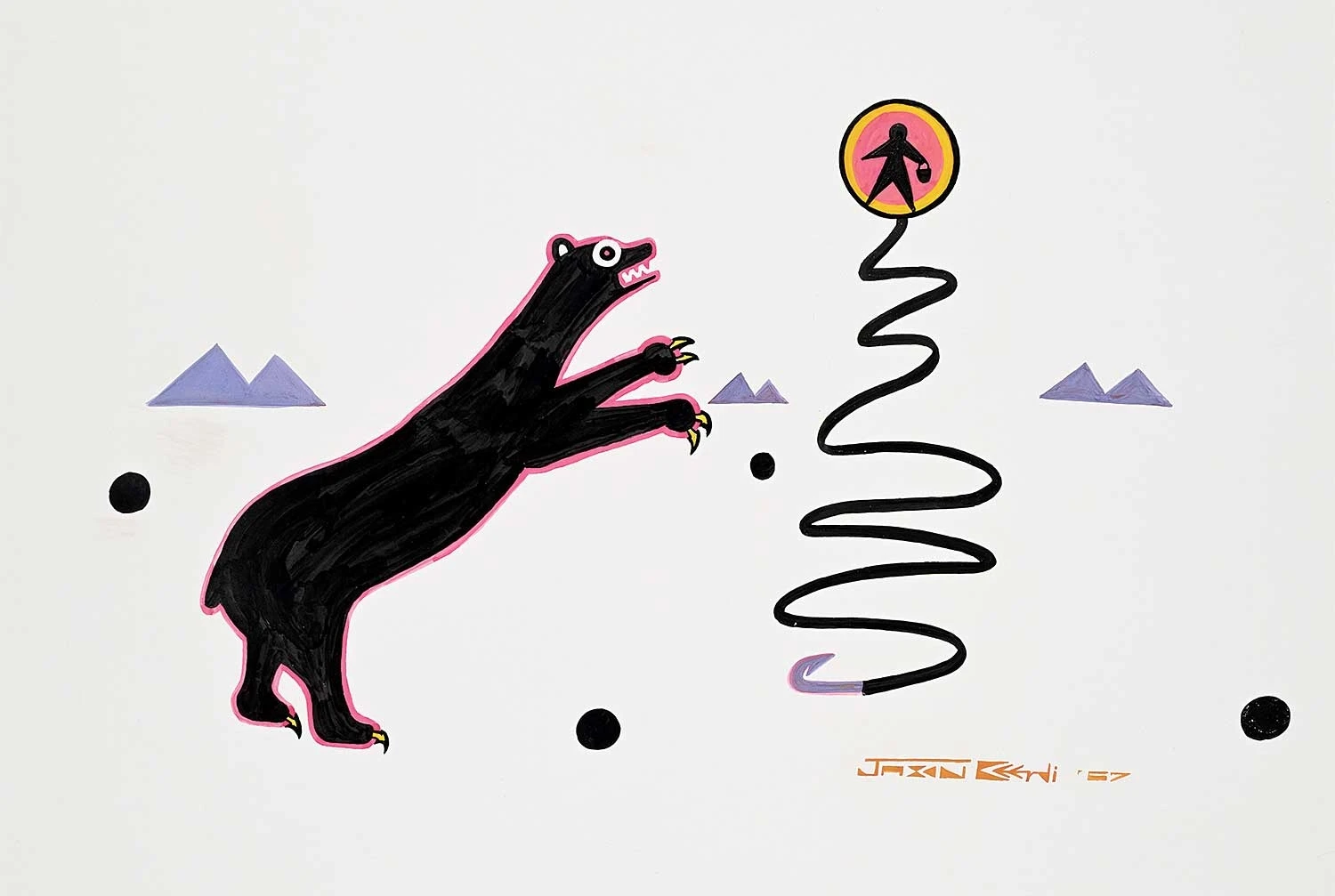

To start, upon the news of his stepfather’s death, Jonny is faced with the decision to return home to the reservation or stay in the city where he finds comfort within motel walls and in the beds of strangers. Both locations act as a place for Jonny to express one of his dual identities: his racial otherness or his queerness. In this sense, Whitehead acknowledges Jonny’s existence as a Wacousta (Whitehead 153) figure that possesses both an Indigenous and western identity, as well as a queer two-spirit identity that possesses both the spirit of a man and a woman. However, while Wacousta’s dual identity works in his favour, Jonny becomes repressed by gender conventions acting against him as a two-spirit Indigenous person. Whitehead presents the threat to Jonny’s dual identity through a bear motif which emerges in dreams and natural imagery. The first instance of the bear motif occurs when a young Jonny compares his baseball peers brawling to bear cubs playing. This imagery acknowledges the existence of gender performance that Jonny struggles with. As they play a hypermasculine sport, the boys express their passion for the sport through a friendly brawl, whereas Jonny finds himself on the sidelines, watching and questioning his masculinity because of his lack of interest in the sport. The bear cub also represents kinship in the Indigenous spiritual world, suggesting that Jonny’s emerging sexuality challenges the bonds that are conventionally created between heterosexual men.

This foreshadows Jonny’s cataclysmic dream where he is chased by the bear figure Maskwa. As the bear appears large and domineering, not only does the natural imagery of a bear remind Jonny of his stray from the natural world of the reservation, but it also emasculates Jonny as his performance of femininity and homoeroticism pulls him further away from the childhood mantra forced onto him to “man up” (79). Whitehead depicts a representation of nature that threatens to conquer the colonial subject similar to the embodiment of Wacousta as a natural and violent threat to colonialism. But where Jonny is expected to subdue the bear, he is topped by the bear. This image parallels Johnny’s role in the sexual relationships he pursues, where he is topped by hyper-masculine white men. While Jonny’s body is forcefully invaded by nature, in a brutal dream sequence where Maskwa becomes his sexual partner, Jonny slowly transforms into the bear allowing him to own his body and gain wisdom from it. The natural imagery of the bear becomes a literal definition of a bear that invokes the naturally-masculine homosexual man. In turn, Jonny is capable of embodying certain masculine traits, while also practicing his sexuality. Notably, Jonny embodies the leadership that Maskwa represents in Cree culture through his emotional strength, unyielding will, and courage. This allows Jonny to develop enough confidence to become a leader in a future relationship with a young sexually confused Indigenous boy, who contacts him to help him lose his virginity. As a mentor, Jonny gives him the following advice: “we all got thick skin, but we still gotta let people in” (192). Jonny’s synthesis of identity is not achieved through the act of subduing threats, but by allowing them to enter his body and become a part of him. As Jonny comes to terms with the reality of being two-spirit, he understands himself more and becomes stronger by engaging with certain gender conventions on his own terms. Subsequently, Jonny becomes aware of his maturity upon a visit to his grandmother’s grave: “I’m sorry I never got to show you how I transform” (218). As such, Jonny is able to acknowledge his trauma and work through it, carrying on his wisdom to others like him sharing similar experiences of sexual repression.

Moreover, Whitehead explores the theme of nostalgia through a fragmented timeline, demonstrating how memories of Jonny’s past infringe on his present circumstances and shape his future. The novel is not ordered chronologically; instead, the novel takes the form of a photo album where each chapter frames a different instance in Jonny’s life that affects the building of his identity. Through this form, Whitehead suggests that there is no real time stamp for the process of character building as it is ongoing. From this, Whitehead’s narrative form denounces the idea that certain mindsets can be associated with time periods, specifically the period when colonialism supposedly ended in Canada near the beginning of the 20th century. Jonny’s method of dismantling colonialism is not instantaneous, beginning infancy and spanning his adult life. In presenting the process of decolonization in this way, Whitehead explores a definition of colonialism that is not limited to the dispossession of land, but rather extends to the conquering of the body and mind of its subjects. In doing so, Whitehead subverts Northtrop Frye’s definition of the garrison mentality that separates the natural world of the reservation from the western social world of the city of Winnipeg. This revision pertains to Ahmed’s argument that “emotions are not simply ‘within’ or ‘without’ but that they create the very effect of the surfaces or boundaries of bodies and worlds” (Ahmed 117). As such, Jonny’s body becomes a form of garrison where his skin acts as a boundary that contains and shelters his identity from the outside world that threatens to claim him to conventions of gender and race.

This relationship between time and character building can be seen through the imagery of water throughout the text. Water becomes a medium that imitates the continuous flow of time, thus, lessons learned in childhood return in adulthood. An example of this is explored through Jonny’s practice of cleansing the soul through sweat, similar to visiting a sweat lodge. Through this practice, Jonny becomes an abject body, a term coined by Julia Kristeva in her essay “Powers of Horror.” She defines the abject as “the place where meaning collapses,” the place where “I” am not. The abject threatens life; it must be “radically excluded” (Kristeva 1982, 2). In the book The Monstrous Feminine (1993), Barbara Creed places Kristeva’s definition of the abject within the context of its role in the human body: “The ultimate in abjection is the corpse. The body protects itself from bodily wastes such as shit, blood, urine and pus by ejecting these things from the body just as it expels food that, for whatever reason, the subject finds loathsome” (Creed 55). From this, Creed draws attention to the uncleanliness of bodily fluids as a symbol for bits of identity that cannot help but seep out of the body despite the necessity to repress them to maintain order. As a young teen, Jonny is prohibited from entering a sweat lodge to cleanse his body of traces of alcohol because he is wearing a skirt in an immodest display of femininity. As a result, Jonny is prohibited from exercising the natural human process of sweating. In doing so, the elder that mediates Jonny’s practice of sweating embodies an internalization of the selective oppression of colonist mentalities that have governed Indigenous communities for generations. Jonny expresses the hypocrisy of his elder’s advice to humble oneself when faced with a body of water: “But water was always a shameful thing for me: to piss, to sweat, to spit, to ejaculate, to bleed, to cry. How in the hell do we humble ourselves to water when we’re so damn humiliated by it?” (Whitehead 66). The sweat lodge showcases the hypocrisy of the wisdom propagated in Indigenous culture, of humbling oneself to nature when the most natural part of one’s body and identity is shunned. In this sense, Jonny acknowledges that by prioritizing natural order, the human body, and by extension the soul, are often disregarded from being a part of nature. Where this incident is aimed to repress his identity, Jonny does not internalize it as such, and in fact, Jonny returns to the sweat lodge psychologically through sex. He recounts his first sexual encounter as follows: “His transforming body wrapped around me, blanketed me, made me sweat ceremonially” (17). Jonny’s sweat in particular grants him comfort that extends outside of the reservation through sexual acts in Winnipeg, thus becoming a symbol of liberation and hardship. Sweat becomes a symbol of the parts of Jonny that he is forced to contain. Through sweat, Jonny is able to blur the boundaries of place, allowing for his indigeneity as well as his sexuality to be practiced wherever he goes. It is through the process of accepting its expulsion from the body that sweat becomes a point of attraction for Jonny towards his sexual partners. As they sweat together from sexual passion, Jonny is attracted to the release of conformity from the body, as well as the ceremony that cleanses the soul from feelings of repression.

Further on, as Jonny continues to explore his body, bodily fluids like sweat help Jonny reflect on where he feels most at home. This pertains to Whitehead’s bigger project of dismantling the colonial mindset by rebuilding the home when the subject has no land left to govern. The body becomes a medium through which this can be accomplished. Jonny’s body becomes part of an ocean, a body of fluids that connects him to his queer and Indigenous neighbors. Abject bodily fluids, as they are composed of water, become a matter that unifies bodies like lands, together. Most notably this connects him to his mother, as demonstrated when a young Jonny sits in the bath with her and reminisces the feeling of being in her womb: “Here in my bathtub alone, I think of Momma, I think of those rapids. (…) I think of how water crafted this whole damn planet, carved it into animals. I think of home” (68). In doing so, Jonny absorbs the dirt, sweat, blood, and tears from his mother, suggesting a definition of home that draws on faults and traumas to build connection. Kristeva writes in her essay that “The purifying recognition of the maternal, or jouissance, is a sexually painful, nostalgic acknowledgement of the maternal achieved through the semiotic” (Kristeva 5). Jonny recounts a visceral description of intergenerational trauma that is passed on, down to every molecule of water that carried and bathed Jonny as a child: “We’d cuddle in the tub until the water turned cold and opaque, until our nipples turned to points and our fingers pruned like Kokum’s” (Whitehead 67). But where the leaking body of his mother makes him remember an upbringing rooted in trauma, Jonny inserts a new layer of his own trauma by incorporating residues of semen in the bath water that enters the drain, and ultimately a bigger body of water that connects Jonny with the world and other repressed characters like him. Sitting in the bath water, Jonny is reminded of the Red River, a traumatic part of Cree history that he describes “gushed blood and guts and catfish” (65). From his use of grotesque and abject imagery in this passage, Whitehead builds upon a bigger message that uncovers the underlying power of interconnectedness as a source for healing. Shared trauma becomes a facilitator in forming deep bonds between people as it allows them to relate to each other and acknowledge that they are not alone in their experiences. As such, Whitehead proposes a method of healing from trauma, by transforming it into love. In his case, Jonny learns self-love and finds a home within himself that allows him to make room for love with those around him. As Jonny returns to the reservation, accepting his home, he tells Tias, “Funny how an NDN ‘I love you’ sounds more like, ‘I’m in pain with you’” (88). And just so, Jonny understands that everyone around him has a past scarred with trauma, but the root of his resides with his mother. Upon his return home, Jonny reconciles with his mother on the reservation as she tells him: “we both born from a wound” (200). The feeling of home is associated with pain and residues of it communicating a theme of nostalgia. But from this pain, love, and kinship are also given the opportunity to flourish. Jonny says: “Sometimes the strangest thing about pain, that sites of trauma, when dressed after the gash, can become sites of pleasure” (179). In the few remaining pages, Jonny and his mother undergo an unsheathing of emotions, where their traumas in all of their rawness, are released from the body: “every bit of breath, stink, and smoke came rushing forth from her belly” (203). From this, Jonny begins the journey of healing his relationship with his mother as they both show their vulnerabilities, share their pain, and build trust that allows them to move forward to fill the “blank pages” (219) with the stories awaiting them.

In closing, Jonny’s abjection becomes a medium through which Joshua Whitehead allows for feeling and identity to pour out of the body, thus breaking free from the reigns of colonialism that represses marginalized bodies. To fulfill his bigger project of dismantling colonialism, Whitehead starts by acknowledging Jonny’s dual identity and how social order has threatened to control his body through a bear motif. However, by becoming the bear, Jonny accepts his body as a home, allowing for his identity to pour out of it like sweat cleansing the soul. After accepting his identity, Jonny becomes connected to others around him with pasts rooted in the traumas of colonialism that Whitehead presents through the imagery of water that connects oceans. Whitehead writes a semi-autobiographical text that stitches holes left from the wounds of Canada’s colonial past. While its scars remain, Whitehead’s story takes the next step into the healing process that utilizes natural imagery and visceral metaphor to draw light and beauty to its rawness.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. “Affective Economies.” Social Text, vol. 22, no. 2, 2004, pp. 117-139. Duke University Press.

Creed, Barbara. The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. Routledge, 1993.

Kristeva, Julia. “Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection,” trans. Leon S. Roudiez. Columbia University Press, 1982.

Richardson, John. Wacousta. McClelland & Stewart Inc, 1991.

Whitehead, Joshua. Jonny Appleseed. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018.