By Safna Mama

In his novel The Scarlet Letter, Hawthorne captures the counterintuitive Puritan ideal of those in Hester Prynne’s colony: sins against God can be forgiven and forgotten by man. Throughout the novel, Hawthorne brings to light the hypocrisy of the balancing act between viewing God as an all-powerful, providential figure and the religious men in power as arbiters of all justice. One of the key ways Hawthorne demonstrates this conflict is through illustrating how in Hester’s colony, labor and servitude are given power and importance akin to that of the religious institutions’. Hester’s community is not loyal to God alone; they also worship labor. This portrayal has three important implications: firstly, the power given to labor means that just as one can find salvation through praying to God, they can also find salvation by working to be productive. Hester then capitalizes on this veneration of labor and uses her skills as a seamstress to go against God’s will: in this case that she be forever punished and marked with shame for her sin. Finally, Hester’s work highlights the hypocritical attitudes of the community, as once she creates something they need or want she is a provider of “fashions” and no longer just a pariah (Hawthorne 95). An important distinction I wish to make clear is related to the Puritan work ethic. Although the Puritans deemed labor an important avenue for God to provide salvation to those who suffer, this paper highlights how Hawthorne subverts this idea. Hester’s labor is not a way in which she suffers, instead it is a way for her to overcome suffering and work around her punishment (Gini).

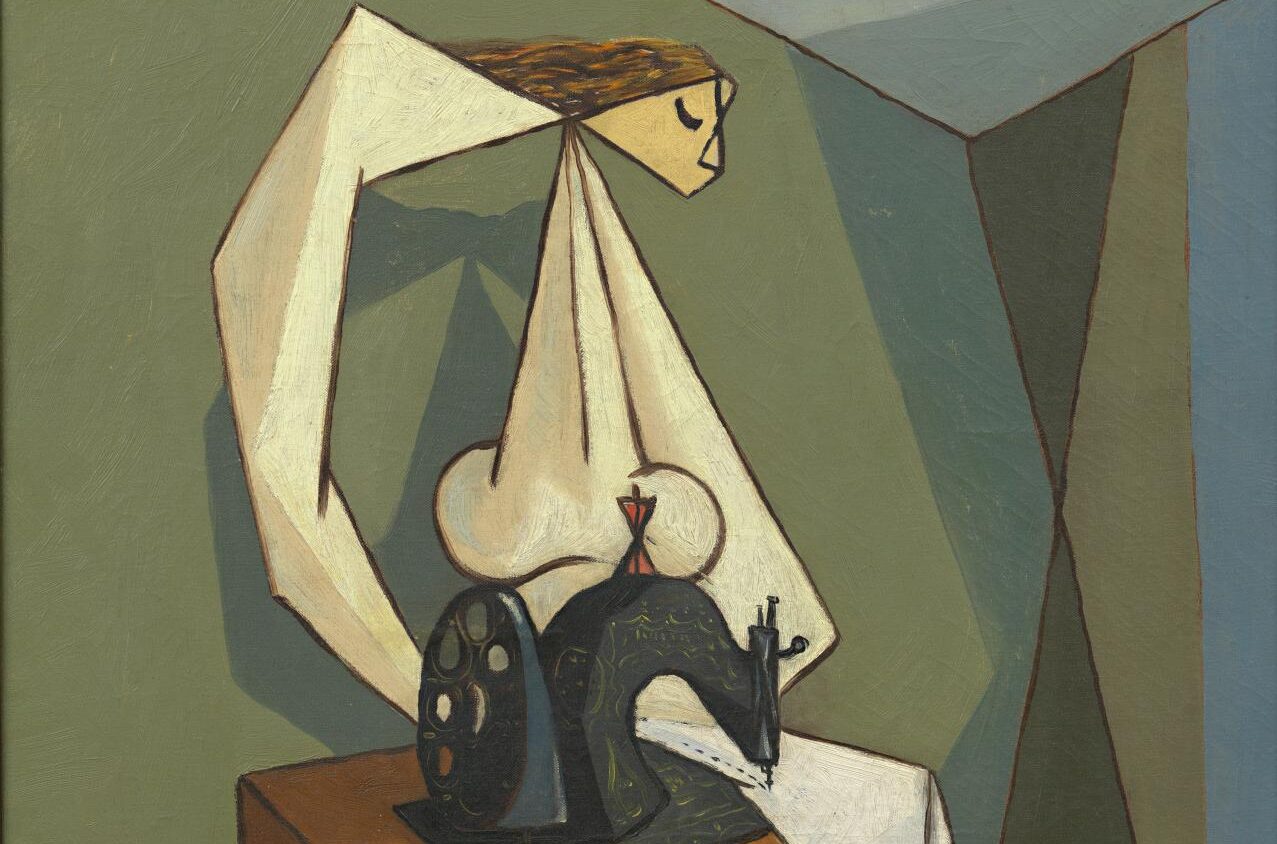

Hawthorne demonstrates the paramount importance of labor in the community by drawing a parallel between labor as an institution and the institution of religion. At the start of the novel, Hester’s work as a seamstress is her salvation, allowing her to feed herself and her child, but it is also used to reinforce her low status and isolation, much like religion itself. In the initial days after her release from the prison, Hester tries to redefine herself by crafting her identity around the clothes she makes rather than the sin she committed which displays labor’s transformative power. She begins to “fill a gap” by providing embroidered gloves for magistrates, apparel for dead bodies, and baby linen (Hawthorne 95). While her creations provide some status, the transformative power of labor is most clearly evidenced by what Hester cannot make: wedding dresses and veils (96). The ban on an “impure” woman making anything for a pure bride demonstrates the intangible aspects of Hester’s creations. Everything she makes is a part of her, as though the veil made by her hands committed the same sin she did. The false virtue of the colony is revealed in how Hester’s labor is selectively defined as “fashions” or markers of her impurity depending on when it suits them (71, 95). If a wedding veil made by Hester is imbued with her sin and will corrupt a bride’s purity, why does this not apply to a magistrate through his gloves? It becomes clear that standards of purity are not universal; they only apply to women who sin against their traditional role, highlighting how servitude is used by those in power in the same way that religion is. It is not unacceptable that Hester broke God’s rule of purity because that rule applies to all; instead, it is unforgivable that she defied societal expectations of feminine subservience. Hester’s labor practices bring this distinction to light; if she has broken man’s rule then it becomes clear how she can gain forgiveness through man. Although labor has the same unequal power structures as religion, it has another similarity. Labor is accessible to all, even social pariahs. This principle enables Hester’s eventual salvation as she uses labor the way the ministers use religion: leveraging its importance in the colony for her own personal gain.

Hawthorne asserts the importance of labor by depicting Hester using her skills as an embroiderer to save herself in the physical world and to gain spiritual salvation. This latter salvation is explained through Laura Powell’s analysis that Hester uses her skill in embroidery to become the “perfect feminine ideal” (Powell 27). This feminine act of servitude is what causes the magistrates to allow her to stay in the community. While Powell analyses the self-serving nature of the community, I expand on this argument by suggesting that although Hester did use labor to gain some level of forgiveness from the community, this was not her end goal. She did not serve the magistrates and villagers because she felt that this would provide her redemption. She only served them so that they would allow her to stay in the village: she believes that only in this land could she “purge her soul” of sin and gain the spiritual salvation she desires (Hawthorne 93). The nature of salvation in the novel is another example of hypocrisy of the Puritans, present even in Hester, and can be understood by looking at early criticism of the novel in Christian journals like The Christian Register and Brownson’s Quarterly Review (Smith 137). These journals claim that The Scarlet Letter misrepresented the idea of salvation from within. The articles stated that the relationship between the individual and God as a way to gain redemption was not present in the text and therefore true meaningful redemption was missing from the novel (139). I argue that the reason it was thought to be missing was because Hawthorne demonstrated the process of redemption enacted through labor instead of God. The Puritan ideal of redemption through Christ is gained from a personal, internal process; however, Hester’s belief that it was necessary to stay in the village to gain redemption makes the process an external one. In this context, salvation is dependent on the sinner’s relationship with society rather than with God. The focus on the land she occupies further reinforces the man-made nature of salvation; Hester is tied to a physical, tangible location and not to any abstract or spiritual higher powers.

Hester’s labor allows her to redefine what the “A” represents, highlighting both its power and the colony’s self-serving piousness. Despite meaning “Adulteress,” the earliest descriptions of the “A” in the Custom House introduction describe it with a positive connotation, highlighting its “wonderful skill of needlework”; the “A” is always a symbol of labor for the skillful embroidery that it contains (Hawthorne 33). Despite this initial focus on beauty, for the people in the colony the “A” still primarily serves as a “mark of shame” (71). However, as they slowly realize Hester’s talent is being wasted when it could instead serve them, the community disregard the punishment decreed by God. The “A,” originally a symbol of sin, eventually becomes an advertisement of her “delicate and imaginative skill” (94). During Hester’s first interaction with the public after being released from prison, the “A” is described as being “fantastically embroidered” and “enclosing [Hester] in a sphere by herself” (60). Although the “sphere” does highlight Hester’s isolation, the preceding descriptions portray her labor as her protector, drawing attention away from her sin to her skill. Eventually, as Hester exploits the gap in the market for her skills and uses them to redefine herself, the “A” starts to mean “Able,” directly disregarding the ministers’, and therefore God’s, will that it forever be a symbol of her shame (196). The colony is unable to disparage a person who works for them or to resist the beauty of her creations; slowly the tangible beauty of the “A” overpowers the intangible shame it symbolizes.

As the novel progresses, Hester’s relationship to her work becomes more complete as labor becomes an “armor” that protects both her and her daughter. Pearl pointing to actual armor and claiming, ‘“Mother,’… ‘I see you here”’ highlights the protective role Hester plays in her life (127). Pearl pointing this out is significant because she is the embodiment of Hester’s sin, and the root of her pain. Her childlike innocence allows her to see only what her mother has provided her. Through her daughter’s love, Hester becomes a saviour not a sinner. Pearl’s comment allows for Hester to be transformed into the A: she stares at the armor and notes how “the scarlet letter was represented in exaggerated and gigantic proportions…the most prominent feature of her appearance” (127). The focus is not only on the shame of the “A,” because it is viewed in the armor, we see its protective powers. Another distinction that highlights the protective nature of the “A” is that when representing Hester’s shame it “burns,” but now it takes over her instead, becoming an armor, one which even her daughter recognises (83, 206). It becomes not just a symbol of religious sin but of hard work and maternal duty. By dressing Pearl in intricate, decadent clothes that she made, Hester partakes in what Powell describes as a “quiet revolution” both by disregarding sumptuary laws of frugality and by putting Pearl on display to show how the girl is not a symbol of shame, but proof of Hester’s love (Hawthorne 105; Powell 26, 29). Labor becomes a means of love and revolution as Hester’s role as a seamstress collides with her maternal role, and both forms of labor create a child that is wild and unashamed (Hawthorne 105, 106). Labor provides redemption because, despite Hester failing in her original “duty” to be a loyal wife, her creative labor gives her a second chance: the ability to redeem herself by fulfilling the second “duty” of a woman, which is caring and providing for her child. Labor allows Hester to transform from a disloyal wife to a loyal mother.

Throughout The Scarlet Letter, while Hawthorne criticizes the rigidity of Puritan religious beliefs, he highlights their hypocrisy by demonstrating how an individual’s life is not only shaped by their relationship to God and purity, but by the work they do and the service they can provide. Labor is not described in terms of a godly duty to work, but a way that Hester Prynne surpasses “God’s” verdict that she forever lives in shame and isolation. Despite claiming that serving God is of paramount importance, the Puritans were unable tocresist the allure of someone serving them. Religious laws may have decreed that Hester’s should be forever marked with shame, but the magistrates declared that her skill in embroidery could not be left to waste. In the end it is clear who had the final say.

Works Cited

Gini, Al. “Protestant Work Ethic.” The SAGE Encyclopedia of Business Ethics and Society. Edited by Vol. 7. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2018, pp. 2792-93. Sage Knowledge, doi: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483381503.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Scarlet Letter. Boston, Ticknor and Fields, 1874.

Powell, Laura L. Sew Speak! Needlework as the Voice of Ideology Critique in “The Scarlet Letter,” “A New England Nun,” and “The Age of Innocence,” University of Nevada, Las Vegas, United States — Nevada, 2011. ProQuest, https://proxy.library.mcgill.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/sew-spea k-needlework-as-voice-ideology-critique/docview/876194228/se-2.

Smith, Lisa Herb. “‘Some Perilous Stuff’: What the Religious Reviewers Really Said About ‘The Scarlet Letter.’” American Periodicals, vol. 6, 1996, pp. 135-43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20771088.