By Isabelle Lamont-Lennox

The Antebellum era of 1815 to 1861 in the United States brought forth a cultural endorsement of white children’s play and leisure time within the domestic sphere, a response to the emergence of a social reconstruction of white and black childhood during this time. By situating black childhood as ‘deviant’ and white childhood as ‘innocent,’ American childhood became racialized and segregated. Toys and dolls helped establish these social contracts, as ideas circulated regarding how material objects of play could be useful to educate children on social norms and ‘proper’ behaviour. White hegemonic culture facilitated the production of children’s toys to reinforce racist ideologies in order to preserve power. As a result, children’s play became immersed in the world of material objects that were often coded with racialized stereotypes. These corporeal objects of play perpetuated racial stereotypes that naturalized whiteness as ‘neutral’ by promoting an explicit ‘othering’ of blackness. Through analysis of paper dolls manufactured during and following this period, this paper explores how racialized toys were mechanisms for indoctrination to white dominant ideology in American childhood during the 18th and 19th centuries, specifically through racist caricatures that essentialized blackness as inferior to whiteness.

In her book Beyond the Boundaries of Childhood, Crystal Webster negotiates the reformulation of white and black childhood during the Antebellum era. She discusses how economic and social contexts in the United States created conditions that designated different sites for play and leisure for white children versus poor children and children of colour (17). She notes that children of colour and poor children “played outdoors in spaces that were not designated for children, such as streets in urban cities,” a contrast to white children who “played indoors under adult supervision” (17). Webster argues that these conditions of play emerged alongside evolving social attitudes regarding childhood during this era. For white parents, indoor objects of play became a way to educate their children on the social behaviour of adults, developing ideologies that their children would take into their adult lives. Paper dolls are toys that were highly effective in this regard due to the ability of manufacturers to construct where and how children played with them, restricting imaginative potential and enforcing a specific behaviour of play. The delicacy of the paper doll’s material designates it as an indoor activity due to paper’s tendency to break down or disintegrate when in contact with water or other substances found outdoors. Therefore, it is unlikely that these dolls were targeted at marginalized children whose spaces of play were more likely outdoors during the Antebellum era. In light of this, middle or upper-class white children’s play within the domestic sphere made them the targeted audience for indoor material objects like paper dolls.

Paper dolls date back centuries according to Judy Johnson from her article “The History of Paper Dolls” from The Doll Source Book. In the mid-1700s, wealthy aristocratic women in France would entertain themselves by making dolls and clothing out of paper (245). Johnson notes that during that period, handmade paper was costly and was typically reserved for members of the upper classes. The onset of the Atlantic slave trade made paper production more affordable through the rapid development of new technologies, and by the early 1800s, paper was being mass-produced. In 1810, “Little Fanny” was the first paper doll to hit industrialized markets by S & J, a toy manufacturing and children’s book publishing company (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Source: Hanson, Marianne. The History of Little Fanny. March 24, 2020. Special Collections Blog. https://specialcollections.blogs.brynmawr.edu/2020/03/24/the-history-of-little-fanny-make-your-own-paper-dolls/ .

The dolls were sold for six shillings and sixpence, equivalent to roughly forty dollars today (Hansen 2020). “Little Fanny” embodied all of the characteristics of the ideal child at the time; her delicate white dress and sweet pink ribbon signify her purity, while her rosy cheeks and subtle smile emphasize her childish innocence. As she holds her own little doll, the young white girls towards whom “Little Fanny” was targeted are able to identify with and admire her ideal image.

Fifty years after “Little Fanny” was released to the public comes “Topsy” (Figure 2.1), the first rendering of an African American paper doll to be mass-produced. In 1863, the McLoughlin Brothers, a New York publishing company specializing in children’s books, manufactured and sold “Topsy.” As pioneers in colour print literature, the McLaughlin Brothers sold the doll as a minstrel caricature of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s character of the same name from Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). “Topsy” was not sold on its own; in fact, it was sold as part of a set of two paper dolls, the other being another character from Stowe, “Eva St. Clare.” (Figure 2.2) The differences and contrasts between McLoughlin’s rendering of “Topsy” and “Eva” are explicitly racialized. While “Eva” dons a delicate, fashionable, white dress, “Topsy”’s clothing is vibrantly coloured, with out-of-date patterns and fashion. “Eva”’s rendering mirrors “Little Fanny,” both pale, fair-haired, and wearing white; the two are also positioned with their feet together, with softened arms. Meanwhile, “Topsy”’s feet are apart, her arms are crossed, and her gaze is fixed on the observer. The curvilinear, delicate lines of Eva’s body juxtapose Topsy’s angular and rigid figure. These dissimilarities to “Eva” and “Little Fanny”’s poses function to sexualize “Topsy.” The ink used to depict her skin is very dark, obscuring her facial features and expression. However, the vibrant red exaggerates her lips. This was a characteristic element of racist minstrel caricatures used to emphasize the ‘otherness’ of black people compared with white people. It equally functioned to sustain the dynamics of slavery into the Antebellum period, by delegating “Topsy” as subservient to “Eva” in this manner, reinscribing racial hierarchies. Through the analysis of these two paper dolls, tensions between child-like innocence, purity, deviance, and maturity emerge in their rendering. The “Topsy” doll signifies a sense of deviance and maturity, while “Eva,” inherits “Little Fanny”’s ideal innocence and purity.

Fig. 2.1 Fig. 2.2. Source: McLoughlin Bros. Topsy and Eva St. Clare Paper Doll Set. 1863. American Antiquarian Society.

To better understand how toys and dolls socialize children, examining children’s approach to play is necessary. Taking the paper doll, for example, its form is constricting in terms of imaginative play and accessibility. The way the dolls are constructed limits the capacity of children to be creative and imaginative while playing. Two racialized dolls may come with different clothes that can be swapped, allowing children to imagine new worlds, identities, and freedoms in their play, while paper dolls limit this ability for children, forcing them to play only in the way the manufacturer intended. This is true for McLoughlin’s “Topsy and Eva St. Claire” set. A socio-economic hierarchy is established whilst examining the flooring depicted on the base of each respective doll; “Topsy,” a plain wood flooring, while “Eva,”’ an ornate flooring tile. Instituting each doll’s ‘station’ in an overt way from the offset. In addition, the pair come with supplementary outfits and accessories for the dolls. The design of the clothing and accessories makes it quite apparent whose outfits belong to whom, but how they are manufactured further imposes these dividing rules onto the dolls themselves. Their arms are reproduced on the outfits intended for each respective doll, but their bodies are posed and cut out in a way that does not allow their clothing or accessories to be interchangeable. The endeavour to swap the dresses in Figures 3.1 and 3.2 (below) elucidates the limits to children’s imaginative play with the dolls.

Fig. 3.1 Fig. 3.2. Source: “Edited Simulation of “Topsy” and “Eva” Paper Dolls Wearing the Other’s Additional Dress.” 2024. IMG.

Their original clothing emerges beneath the other’s dress, and their arms and hands are exposed in the cut-out, meaning that children playing with the set could not reasonably envision them wearing the other’s clothes. Each doll was thus designated the clothing which was expected of each girl’s class and positioning. In this way, children engaging with this set of paper dolls can only realistically imagine these two dolls exactly as they were manufactured. The sociological effects of this kind of physical and imaginative constraint while playing results in an understanding of a clear dichotomy between “Eva” and “Topsy,” underscoring the inferiority of “Topsy”’s deviance and “Eva”’s innocence. Making “Topsy”’s clothing and accessories out of fashion further emphasizes her abnormality and ‘otherness’ to the white American children engaging with her. It limits the possibility of “Topsy”’s escape beyond the limits of the segregated paradigm, which perpetuates her racialized subservience to “Eva.” Children playing with “Topsy” are not able to imagine her outside these limitations, even as they ‘make belief.’

Doris Wilkinson evaluates how dolls are “strategic cultural mechanisms for indoctrination” (103) in her paper “Racial Socialization Through Children’s Toys.” She draws from Sigmund Freud, who argues that children gain ‘impressions’ from their play, which they adopt from real life. According to Freud, they absorb “the strength of the impression and… make themselves master of the situation”(Freud 16-17). This means that children’s play is immersed in these imposed ‘impressions,’ (or social dynamics) that they observe in real life and then replicate and enforce while engaged in play. For Wilkinson, children’s play becomes “analogues and illustrative encounters in adult arenas involving role-taking self-versus other concepts, and wish fulfilment” (97). As previously addressed, toys and dolls after the American reconstruction of childhood in the early 1800s were manufactured to socialize and educate children. Parents bought toys to educate their children on domestic roles and to develop their understanding of social constructs and hierarchies. Dolls themselves are historically a uniquely domestic class of toy because of their implied gendered roles within the household and how they emulate women’s behaviour. Understanding how race is involved in the white home is an important part of how America’s white hegemony during this period participated in, and helped to facilitate, the sort of toys that were being manufactured for white children.

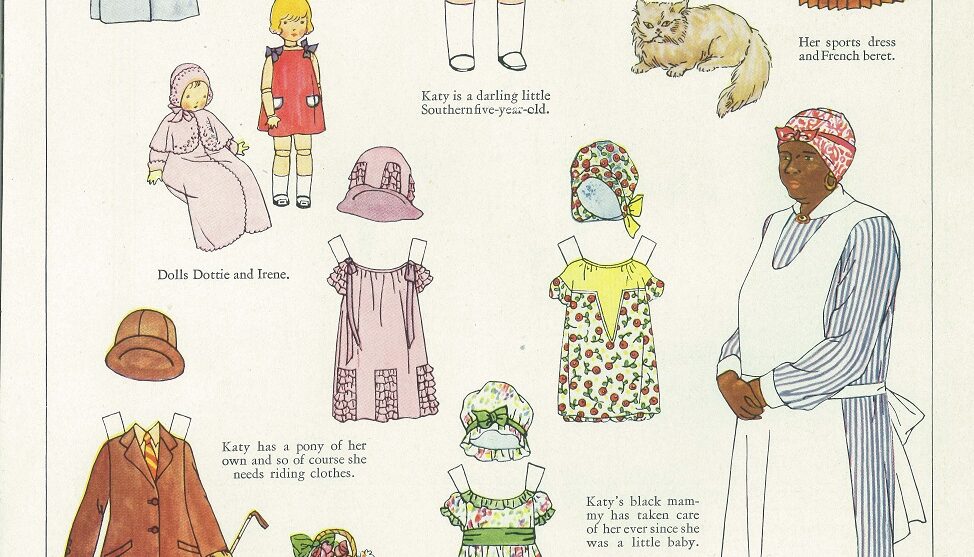

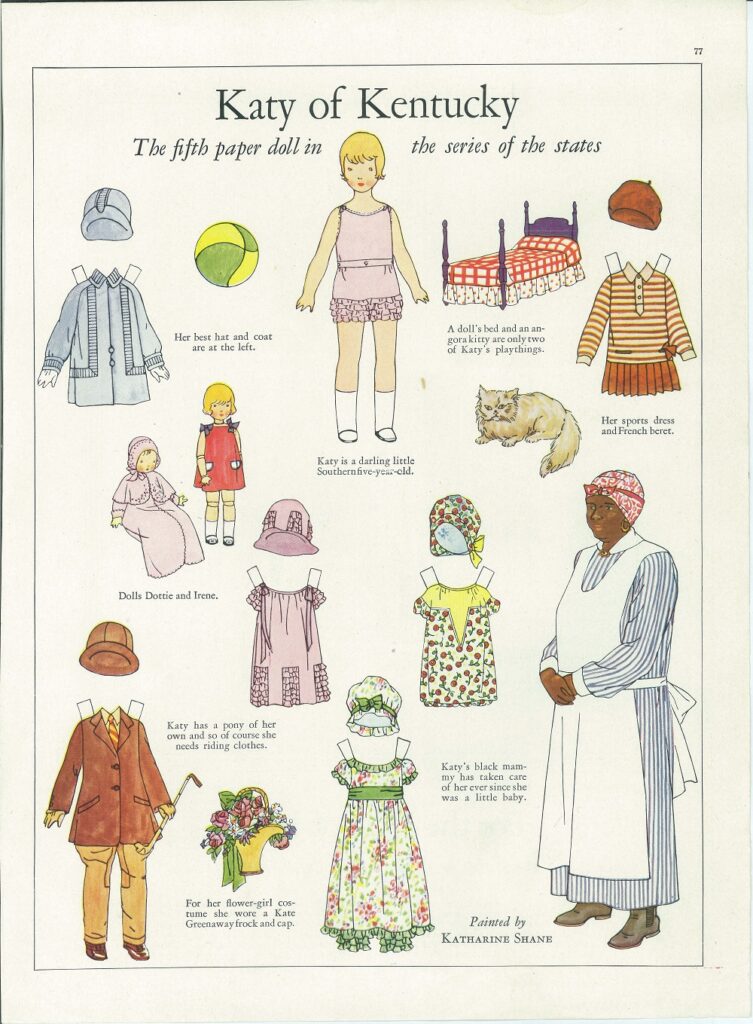

Some of these kinds of toys employed the image of the ‘Mammy’ or ‘Mammie’ figure, which emerged alongside the “Aunt” or “Auntie” caricature of black women as domestic labourers and caregivers. Deeply rooted in American slavery, slave-holding houses often positioned enslaved black women in domestic and child-care work. The ‘Mammy’ caricature’s origin is difficult to pinpoint, but one of the earliest and most well-known archetypes comes from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, like “Topsy.” The ‘Mammy’ caricature is adapted from Stowe’s characterization of Aunt Chloe. Aunt Chloe, Uncle Tom’s wife, is characterized as a pious, faithful wife, a devoted mother, and an excellent cook. This was the foundation for the traits featured in the ‘Mammy’ stereotype. Paper dolls began to create paper dolls of the ‘Mammy’ and ‘Aunt’ as caricatures of caregivers to white children. One example of this is seen in Figure 4 from Woman’s Home Companion in 1927. This paper doll set,

Fig. 4. Source: Shane, Katherine. “Katy’s black mammy has taken care of her ever since she was a little baby.” 1927. Woman’s Home Companion.

“Katy’s black mammy” is unnamed, thus muting her identity. She is defined by her role as caretaker to “Katy of Kentucky.” “Katy’s black mammy” wears an apron and is rendered with notable minstrel qualities: aggregated red lips and hoop earrings just like “Topsy” (fig. 2.1). Like “Topsy” she is positioned with her legs slightly apart, and her posture rigid, adopting the same sexualizing effects in this rendering. This set does not include any accessories for “Katy’s black mammy,” leaving no creative escape from her domestic/caretaking roles during play. By adopting these caricatures, the paper dolls signal to children to restrict black women to these domestic and/or child-caring roles during their imaginative play. ‘Mammies’ almost always go unnamed, erasing their individual identity and suggesting that black women are interchangeable. In this way, the ‘Mammy’ caricatures essentialize black women, training white children to see all black women as ‘caregivers, ’ ‘aunties,’ and domestic labourers.

By characterizing black children as ‘deviant’ and ‘mature’ and black women as ‘Mammies’ or domestic labourers, paper dolls embedded racism into childhood during the Antebellum era. The effect of material culture naturalized whiteness as the standard and played an important role in preserving white hegemony in the 18th century and early 19th century. The extent to which the material culture of childhood–like toys and dolls–contributes to children’s understanding of the social world around them should not be underestimated. When producing and manufacturing these material objects of play, it is critical to consider how children can or will engage with the toys and what meanings they will derive from the toys themselves. After all, it is evident that children’s toys and dolls are as much playthings as they are educational tools which influence and promote social norms to children for better or for worse.

Works Cited

Bernstein, Robin. Racial Innocence, 2 June 2020, https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9780814787090.001.0001.

Hansen, Marianne, and Marianne Hansen. Special Collections Blog, 24 Mar. 2020, specialcollections.blogs.brynmawr.edu/2020/03/24/the-history-of-little-fanny-make-your-own-pa per-dolls/.

Johnson, Judy M. “A Brief History of Paper Dolls.” The Doll Source Book, Betterway Books, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1996.

Webster, Crystal Lynn. Beyond the Boundaries of Childhood: African American Children in the Antebellum North. University of North Carolina Press, 2021. Wilkinson, Doris Yvonne. “Racial socialization through children’s toys: A sociohistorical examination.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, Sept. 1974, pp. 96–109, https://doi.org/10.1177/002193477400500107.