By Ava Ellis

Content warning: This essay contains mentions of racial violence and slurs.

Art and literature produce a connection between producer and audience. For Black authors and artists, this often reflects shared histories and struggles in their communities. How audiences engage with work that is deliberately unsettling and jarring becomes a critical challenge in their work. Aimé Césaire’s Notebook of a Return to the Native Land (1939) and Kara Walker’s silhouette tableaux directly confront this question with their use of violent imagery. I argue that transgression and violence are powerful tools for the Black scholar, capable of inciting action, and either polarizing or uniting their audience. The notion of homeland and the use of violence in Césaire and Walker’s works are central to their critiques of oppression, ultimately shaping how their audiences engage with themes of resistance and liberation. Through my analysis, I determine that these methods evoke powerful responses and reveal tensions between revolutionary action and its consequences. I will analyze visceral imagery from Notebook alongside the silhouetted figures in two of Kara Walker’s tableaux to illustrate my argument. I will also build on Edward Said’s theory of exile as a condition of alienation and critical perspective, along with Walter Benjamin’s concept of violence as a means of both destruction and historical rupture, to support my claims about displacement and the political force of artistic expression.

- Is There a Homeland for the Black Scholar?

Césaire and Walker’s relationship with home is shaped by their artistic perspectives. Walker created art within the U.S., while Césaire writes far from Martinique, revealing how time and location influence diaspora narratives. Césaire moved to Fort-de-France to attend Martinique’s only secondary school, and later pursued higher education in France on a scholarship. Mahmud Al Hasan argues that Black scholars’ pursuit of education in Western institutions exposes them to the perceived “superiority” of whiteness, which pressures them to imitate their colonizers in order to achieve comparable socio-economic status (12-13). With a new perspective gained in France and pending his return to Martinique, Césaire began writing Notebook in 1939. The long poem, described by André Breton as “nothing less than the greatest lyrical monument of our time,” is both a critique of colonialism and a declaration of Black identity (Césaire 2001 xiii). This tension between distance and belonging shapes the themes of Notebook.

The poem reveals Césaire’s complicated relationship with his homeland, an island marred by colonial destruction. Although he was not forced to move to France, Edward Said’s writings on exile provide an interesting parallel. Said describes exile as a secular and “unbearably historical” condition that isolates individuals from their roots and forces them to reconstruct their identities (181). Exiles are cut off from their roots, and yearn to piece together their lives, usually doing so by viewing themselves “as part of a triumphant ideology or restored people” (Said 183). Notebook became a manifesto for Césaire, a way to reclaim his belonging to a homeland that felt increasingly distorted and inaccessible in France. Said’s notion of exile as displacement and identity reconstruction mirrors Césaire’s use of Notebook to connect to a homeland that had become fragmented by colonial influence. Furthermore, Césaire’s time away from Martinique challenged whether it could retain its status as a homeland. This sense of displacement extends beyond Martinique, raising broader questions about the Black scholar’s relationship to home and identity across the diaspora. Cesaire reflects on the difference between himself and his African counterparts, acknowledging, “we’ve never been Amazons of the king of Dahomey, not princes of Ghana…. Nor wise men in Timbuktu under Askia the Great, nor the architects of Djenné” (27). Away from Martinique, Césaire confronts the unsettling realization that he may have no true home to return to, at least unlike other scholars of Négritude like Léopold Sédar Senghor. With ancestral ties from Africa cut off by Atlantic slavery, where can the Black scholar of the Americas call home?

Kara Walker’s separation from her subject matter is temporal rather than physical, reflecting a different kind of distance than Césaire’s. While Césaire’s exile from Martinique is marked by physical separation, Walker’s work engages with the past from a temporal distance, as she examines race, class, and gender in the Antebellum South. She became one of the youngest recipients of the MacArthur Fellowship, gaining international acclaim for her black silhouette tableaux at just twenty-eight years old (Repetto 7). Her work examines race, class, and gender in the Antebellum South, depicting the grotesque realities of slavery and racism. At thirteen, Walker moved with her family to Stone Mountain, Georgia—the birthplace of the modern Ku Klux Klan—which greatly influenced her art (Repetto 7). She revisits the past to comment on the ideologies that shaped the United States. Unlike Césaire’s self-exile, Walker’s work is a historical excavation, rather than a recounting of her lived experience. Her homeland is also questionable; it is difficult to claim the United States as a homeland when these histories exist. In addition to the ancestral problems of slavery, Walker’s work reflects on whether a violent country can be a homeland for African American people.

While Walker’s work excavates historical violence, Césaire’s response to his own questioned homeland is more personal and active. Césaire positions himself as a Redeemer figure to his homeland. Malachi McIntosh defines the Redeemer as a singular, privileged, member of the collective—someone with the vision and ability to take action when the crowd cannot (McIntosh 149). Cesaire has gone away, developed his communication, and he says to the land: “If all I can do is speak, it is for you I shall speak” (13). Finding himself in a liminal space between his cultural identity and his new perspective from France, he is forced to see his past as an embarrassing and savage place (Al Hasan 14). The Martinican people are described as weak or inert Césaire realizes that he has the power to give them a voice. He also adopts the persona of Toussaint Louverture, the prominent leader of the Haitian revolution, describing himself as “a lone man imprisoned in whiteness, a lone man defying the white screams of white death” (Cesaire 16). By adopting this persona, Césaire aligns himself with a figure who embodies both resistance and isolation, reflecting the duality of belonging and alienation. As the Redeemer, Césaire’s response to this tension is to take on the role of a voice of salvation.

Walker’s work does not seek to idealize or reclaim a lost homeland; rather, it interrogates how the legacy of slavery continues to shape Black identity. She assumes the role of a historian, documenting the grotesque realities of slavery and racial violence in the Antebellum South. Her tableaux lack clear geographical markers, instead centering on the fractured interactions between Black and white Americans. These figures do not form a collective; their scenes are isolated, and disconnected from broader narratives. Walker critiques the selective memory of history, exposing how certain stories, particularly those of racial violence, are overlooked or erased. Through her silhouettes, she forces viewers to confront these gaps in historical representation and the enduring impact of racial violence. Instead of speaking on behalf of her people, Walker holds up a mirror, revealing the potential for evil within humanity and compelling viewers to confront their own perceptions as they engage with her work.

- The Unsettling Use of Violence

Césaire and Walker’s violence is notably unsettling and jarring. Notebook’s length reflects the protracted experience of colonization in Césaire’s homeland, and his sprawling, punctuation-less verses mirror its unrelenting nature (Banerjee). Césaire introduces the Caribbean as a site of agitation and constriction. It is “the hungry Antilles, the Antilles pitted with smallpox, the Antilles dynamited by alcohol, stranded in the mud of this bay, in the dust of this town, sinisterly stranded” (Césaire 1). The place is desolate and devoid of hope, and his memories reflect even more abject imagery. Lines such as: “So much blood in my memory! In my memory are lagoons” (25) and “My memory has a belt of corpses! and machine gun fire of rum barrels brilliantly sprinkling our ignominious revolts,” (25) refer to a chaotic hellscape, completely subverting expected notions of home. They disrupt romanticized or nostalgic views of the homeland, instead portraying it as a site of trauma, suffering, and perpetual unrest. These illustrate the inescapable weight of colonization, which Césaire likens to a cycle of inertia. Repeated phrases like “at the end of daybreak” evoke hopelessness that traps the colonized in despair (Zahid 87). This inertia creates a resignation to fight for oneself or one’s community, considering it already lost. While Césaire subverts romanticized notions of home, Walker employs violence to expose and unsettle historical narratives.

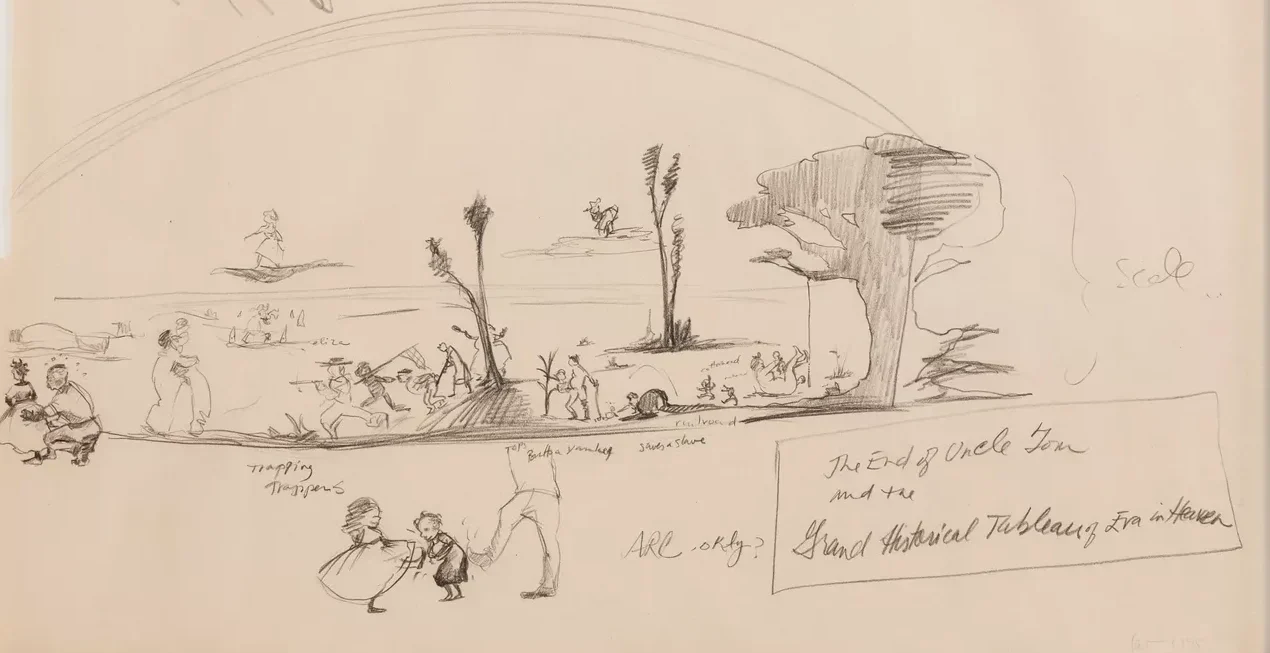

Walker’s work, while also grounded in the violent realities of racial history, presents a different approach to confronting that trauma. Her silhouette tableaux, which seem almost unreal, offer a distinctive form of representation. She believes that the silhouette is a form of truth and its purpose is to intentionally “capture the contour of a figure and function as a form of portraiture” (Repetto 8). Relying on minimal visual information to communicate the sitter’s likeness, however, the form is also a stylistic exaggeration (Repetto 8). The silhouette has a racist history, used to develop one-dimensional, stereotypical portraits of slaves. Walker draws on this, contradicting her violent scenes with the “feminine craft” of elegant portraiture (Repetto 11). This allows her to comment on both the gendered and racial connotations of her subject matter and medium. Furthermore, the simple graphic form forces the viewer to watch the action without any distraction of color or shading. In Gone, An Historical Romance of a Civil War as it Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994) (Figure 1) and The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven (1995) (Figure 2), Walker poses her figures to perform or receive various exaggerated forms of physical or sexual violence. Gone examines the stereotype of the oversexualized and exploited young Black child; it shows a girl with large male genitals, a birthing child, and one performing fellatio on a young boy. The End of Uncle Tom adds to this and also features exaggerated images of men birthing young black boys. Refusing the viewer any moral distance, Walker implicates them in the violence of looking (Wall 280). The large scale envelopes them, offering no escape from each grotesque scene.

Césaire and Walker also refer to internalized violence, evident in their use of derogatory slurs, specifically the “N”-word. Lines in Notebook such as “niggers-are-all-alike, I-tell-you…. Nigger-smell, that’s-what-makes-cane-grow…. Beat-a-nigger, and you feed him” (Césaire 25) expose the colonized subject’s struggle with self-perception. This internal violence conflates Blackness with inferiority. Césaire describes the despair of those in his community who have internalized their subjugation, such as the Black man, a character later in the poem, who says: “You see, I can bow and scrape, like you I can pay my respects, in short I am not different from you; pay no attention to my black skin: the sun did it” (Césaire 45). Césaire conflates Blackness with inferiority, portraying it as something to be apologized for or justified. The speaker’s plea reflects the internalized self-loathing of a community that has internalized its low status. This reveals how colonialism instills a cycle of self-denial, reinforcing both personal and systemic violence. A speaker, the supposed Redeemer of his people is described as “a nigger with a voice clouded by alcohol and destitution” (McIntosh 146). Like Césaire, Walker confronts and reclaims harmful stereotypes. Many racist tropes appear in Walker’s images and titles, including the mammy, the pickaninny, and the “nigger wench.” Titles like the 1995 “The High Sweet Laughter of the Nigger Wenches at Night” and “The Liberation of Mammy” reflect the alter egos Walker assumes in her work. She describes these characters as hers and explains how, as an artist, using and controlling them rescinds their power over her (Dubois Shaw 18). This reasoning also applies to Césaire. By referring to themselves as terms with such violent pasts, the two writers reclaim agency. Beyond the self-referential slur, the violence of their work is also a reclamation of power, controlling the violence that has been systemically aimed at them.

- What is their Aim?

Though decades apart, Césaire and Walker present similar ideas of postcolonialism in the Black diaspora. They both question nationalism and the social and political transformation necessary for decolonization. This also concerns democracy, as decolonization dissolves colonial legacies by returning power to the people. This act is disordered and violent, as it is simply impossible to return to pre-colonial “purity” (Al Hasan 11-12). Violence is therefore a necessary component of each of their aims: Césaire’s for action and Walker’s for reflection.

Césaire’s violence motivates his people to weaponize their resentment and anger, fueling their fight for change. His opening line is vengeful: “Beat it, I said to him, you cop, you lousy pig, beat it, I detest the flunkies of order and the cockchafers of hope” (Césaire 1). He then “turned toward paradises lost,” setting up an active and rebellious perspective that longs for home; a place the cop cannot understand (McIntosh 143). He repeats the trope of the silent Christian crowd, implying that they need a martyr to witness their ruin because, without it, their deaths are in vain (McIntosh 149). However, Césaire was anti-Catholic, believing there was no reconciliation between the Black world and the Catholic Church (McIntosh 150). Instead of a priest, the Martinican people needed a voice from a Redeemer. Césaire’s violence catalyzed an awakening, urging his people to reject passivity and reclaim their agency through collective resistance and self-determination. This culminates in Césaire’s assertion of Négritude—not as an inanimate object like a stone, tower, or cathedral, but as something deeply rooted in the flesh of the people, the soil, and the sky (Césaire 35). Through this declaration, Césaire transforms violence into a force of reclamation, grounding Black identity in the land and body, and calling his people to rise from silence into a movement of resistance and renewal.

While Césaire’s work focuses on the collective awakening of his people, Walker’s approach shifts the focus inward, urging individual reflection on the role of race and identity. Her grotesque motifs imply the social construction of race and the performance of an “imagined identity rooted in ideological fallacies” (Holtzman 3). She plays with and exaggerates tropes for her diverse audience. Walker’s attraction to such stereotypes suggests a resonance with her sense of self, relating to Fanon’s theory of self-fragmentation and being forced to view herself through the eyes of her oppressor (Holtzman 11). This fragmentation is / evident in Walker’s exaggerated portrayals, where the grotesque depictions mirror the internalized distortion of identity imposed by a racially biased society. She places this burden onto her Black audience and elicits uncomfortable reflections on others. Walker’s tableaux weaponize the silhouette’s racist history to create a jarring juxtaposition between aesthetic elegance and grotesque content, implicating the viewer in the violence of representation. Finally, instead of collective action, she inspires introspection on how each viewer is complicit in continual violence.

- How did the diaspora respond?

As a novel, Notebook demands active engagement to uncover its violent themes, complicated further by translation. Walker’s tableaux reach a wider audience with immediate impact. Acknowledging the different media enlightens readers on how form shapes the audience’s encounter with violence—Césaire’s lengthy poem requires sustained engagement, while Walker’s large-scale tableaux confront viewers instantly, leaving little room for detachment. For Césaire, Mazisi Kunene’s introduction to the 1969 publication of Notebook, “But is this not racism? cry the whites, frightened at such an assertion of the blackman’s reality,” reflects a plausible reaction to the text’s self-referential violence (Césaire 1969 10). This response highlights the differing reactions to Césaire’s assertion of the Black man’s reality. Despite widespread praise for Notebook, Césaire has faced criticism, particularly from figures like Raphaël Confiant and Laminaire Moi, who challenged his political stances and his framing of Africa as the center of Black identity. They questioned whether his Négritude was overly nostalgic or whether the tensions in his work, between acceptance and rebellion, revealed an underlying ambivalence toward colonial structures (Zahid 84). However, given the immediacy of colonial oppression in his time, Césaire’s call to anger and action likely successfully resonated with readers confronting the harsh realities of their lived experiences.

Betye Saar and Howardena Pindell publicly condemned Walker’s tableaux as racial and gender treachery, even launching a letter-writing campaign to revoke her MacArthur “genius grant” (Wickham 337). They rejected a satirical reading of Walker’s work, arguing that irony is inappropriate for such themes when institutional racism remains entrenched in the high art world. In a 1997 paper, Pindell accused Walker of catering to the “bestial fantasies” of Black culture constructed by white supremacy (Wall 279). Walker broke away from expectation, following an avant-garde tradition of Black artists foregoing community praise in lieu of their independent visions (Dubois Shaw 7). Because of her temporal distance, Walker may have had more difficulty than Césaire in confronting the entrenched racism and violence of her time. For many, these realities are inconceivable in the present and should not be uncovered. Especially from a Black woman, using these tropes is jarring and can seem like playing into the fantasies of her oppressor with little self-respect.

Building on the complex themes of representation and violence explored by Césaire and Walker, Walter Benjamin’s theory of violence supports the ways their work challenges conventional boundaries. Benjamin positions violence as not only a means to an end but as something beyond conventional notions of justice or law. He distinguishes mythic violence, which perpetuates power and guilt, from divine violence, which “is law-annihilating; if the former sets boundaries, the latter boundlessly destroys them” (Benjamin 64). Both Césaire and Walker align with Benjamin’s concept of divine violence, using their respective mediums to dismantle colonial and racial structures, forcing audiences to confront uncomfortable truths and complicity. Césaire and Walker grapple with the challenges of representation, yet their approaches have sparked ongoing debates about the efficacy and ethics of their methods. For Césaire, the idealization of Africa as a homeland and the ambivalence toward colonial structures in Notebook raises questions about whether Négritude is a genuine pathway to liberation or a nostalgic response to displacement. In contrast, Walker’s grotesque silhouettes employ irony to expose uncomfortable truths about the legacy of slavery and systemic violence. However, her work risks alienating audiences who feel it reproduces harmful stereotypes rather than dismantling them. In Benjamin’s terms, both artists employ a form of “law-destroying” violence; Césaire’s poetry dismantles the colonial order to inspire action, while Walker’s silhouettes shatter sanitized histories, forcing audiences to confront their complicity.

- Conclusion

Aimé Césaire and Kara Walker use violence as a powerful tool to confront and deconstruct the legacies of colonialism. Through Césaire’s long poem and Walker’s silhouette tableaux, they challenge their audience to reckon with the painful realities of Black identity, history, and oppression. Césaire’s self-exile and Walker’s temporal distance shape their respective depictions of violence, with Césaire’s call for resistance and Walker’s grotesque imagery each implicating the viewer in uncomfortable truths. Both highlight the enduring impact of racial violence and the complexities of home within the Black diaspora, reflecting on how art can challenge and ultimately transform societal narratives. The multimedia approaches of Black scholars like Césaire and Walker highlight how violence is a critical means to challenge historical erasure and systemic oppression.

Images

Figure 1. Walker, Kara. Gone, An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart. 1994. Cut paper on wall, © Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Figure 2. Walker, Kara. The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven. 1995. Cut paper on wall, Variable. Collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Works Cited

Al Hasan, Mahmud. “Rediscovering Identity and Restoring African Values through Cultural Resistance: A Postcolonial Reading of Aimé Césaire’s Poem ‘Notebook of a Return to the Native Land.’” Erothanatos, vol. 7, no. 3, 2023, pp 10–22.

Benjamin, Walter. “Toward The Critique of Violence.” Toward the Critique of Violence: A Critical Edition, edited by Peter Fenves and Julia Ng. Stanford University Press, 2021, pp. 39–62.

Césaire, Aimé. Notebook of a Return to My Native Land. Translated by Clayton Eshleman and Annette Smith, Wesleyan University Press, 2001.

———. Return to My Native Land. Translated by John Berger and Anna Bostock, Penguin Books Ltd., 1969.

Dubois Shaw, Gwendolyn. Seeing the Unspeakable: The Art of Kara Walker. Duke University Press, 2004.

Holtzman, Dinah. “‘Save the Trauma for Your Mama’: Kara Walker, the Art World’s Beloved.” Revisiting Slave Narratives II, edited by Judith Misrahi-Barak. Presses universitaires de la Méditerranée, 2007, pp. 377–404.

McIntosh, Malachi. “Migrants as Martyrs: Notebook of a Return to Native Land, The Ripening, I Am a Martinican Woman.” Emigration and Caribbean Literature, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 137–83.

Repetto, Sarah Finer. “‘These Images May Be in Your City next’: Reception Issues in the Art of Kara Walker.” California State University, Long Beach, 2014.

Said, Edward. Reflections on Exile: & Other Literary & Cultural Essays. 2nd ed., Granta Publications, 2012.

Walker, Kara. Gone. 1994. Cut paper on wall, 66 x 92 inches. Private Collection.

———. The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven. 1995. Cut paper on wall. Collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Wall, David. “Transgression, Excess, and the Violence of Looking in the Art of Kara Walker.” Oxford University Press, vol. 33 no. 3, 2010, pp. 277–99.

Wickham, Kim. “‘I Undo You, Master’: Uncomfortable Encounters in the Work of Kara Walker.” The Comparatist, vol. 39, no. 19, 2015, pp. 335–54.

Zahid, Md. Sazzad Hossain. “Intersecting Narratives of Resistance: Aimé Césaire’s Critique of Colonization in ‘Notebook of a Return to the Native Land.’” International Journal of Diverse Discourses, vol. 1, no. 2, 2024, pp. 82–92.