By Adrienne Roy

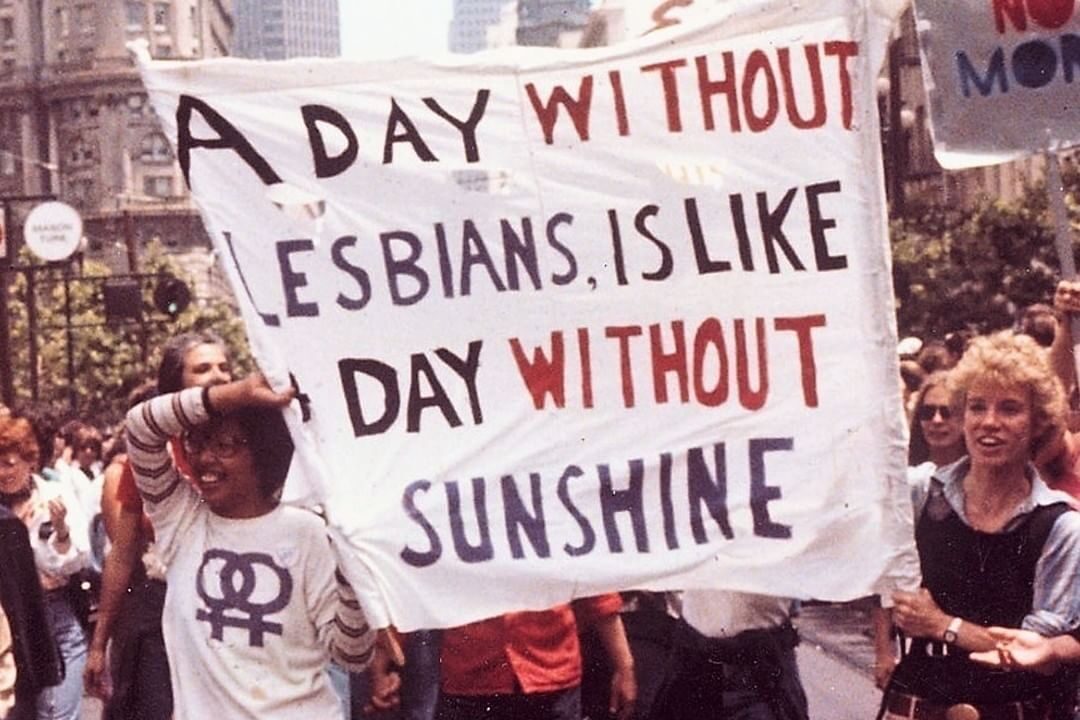

One of the first pieces of lesbian history I encountered was a picture from the San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Parade in June 1979. The picture is of two women raising a banner that says, “A DAY WITHOUT LESBIANS IS LIKE A DAY WITHOUT SUNSHINE” (lgbt_history). This image circulates across my social media feeds throughout the year, and reading it now brings me the same comfort as it did when I was a tween. I cannot, however, find its original publication in the Chicago Tribune or any information on the photographer. A Google search of this slogan brings up a handful of e-storefronts selling pins and t-shirts, and a link to the Instagram account with the post that provides the description I have given. On the surface, the story of this image reaches a dead end. I want to know who those women are and who made the sign. Did they know each other? Where did they meet? Who is the photographer? Why are these details so hard to find?

These unknowns underscore the indispensability of lesbian archives and, more broadly, dispute the relative adequacy of institutional versus grassroots organizations in preserving archival material belonging to or about a marginalized community. The key points of this debate are twofold: the first is the ease with which patrons can access these materials, and the second pertains to the curatorial values, histories, and processes that shape these archives. Although my chosen archive is one that Ann Cvetkovich also examines in “In the Archive of Lesbian Feelings,” I argue that she does not sufficiently evaluate the administrative deficiencies of the Lesbian Herstory Archives (LHA) in favour of affirming its capacity to “produce not just knowledge but feeling” (241). In the seventh chapter of her book, Cvetkovich does not inhabit the separatist stance that many defendants of the LHA hold, but she concludes that “[e]phemeral evidence, spaces that are maintained by volunteer labours of love rather than state funding, [and] challenges to cataloging” are, in themselves, worth more than the objects that codify these histories (268). Theoretically, I agree; in practice, I contend that Cvetkovich’s ethos can lead to the gatekeeping of lesbian experiences. By privileging its physical space in New York City over the objects it houses, the LHA forsakes queer people from outside the city, state, or country. Furthermore, if the LHA were to endorse Cvetkovich’s position, it would perpetuate the issue of metrocentrism in queer historiography precisely because the archive is located in what is frequently considered to be the birthplace of gay liberation.

Despite the counter-hegemonic potential of Cvetkovich’s argument, it presents methodological discrepancies that do not account for a researcher’s capacity to wield institutional archives in an empowering way. Thus, I propose that we should not treat grassroots archives as stand-ins for institutional archives with gay and lesbian collections (Cvetkovich highlights the New York Public Library and Cornell University’s Human Sexuality Collection). Rather, I propose that institutional archives and grassroots archives are mutually constitutive—that both feeling and knowledge have a place in a queer archive. To sustain this point, I will use Johannah Bird’s article “Indigenous Relational Methodologies and Archives” as a theoretical compass. As an Indigenous person of the Peguis First Nation, Bird delineates how both white supremacy and systemic heteropatriarchal subjugation have permeated her archival research. In turn, she suggests criteria that marginalized individuals might seek when investigating their own histories.

Determining the exact definition of an archive is easier said than done. The term frequently refers to a collection of documents, evidence, and ephemera, or the place that holds those fragments. This dual connotation contextualizes Johannah Bird’s assertion that the “practices and procedures of archives facilitate certain kinds of relation—or disrelation—that reflect larger colonial histories” (42). While Bird addresses how the archive is a “site of relationality” from an Indigenous perspective, the need she describes to “access these items in their materiality” is one that Cvetkovich alludes to in “In the Archive of Lesbian Feeling”, writing that “the LHA aims to provide an emotional rather than a narrowly intellectual experience” (Bird 42; Cvetkovich 241). When Bird discusses her time with the Church Missionary Society (CMS) fonds in Ottawa, she recalls how the staff would not let her consult original letters and diaries written by the Cree, Métis, and Anishinaabe people she was studying because someone had already digitized those materials, making them available on microfilm (43). Bird’s experience illustrates how certain relationships with and in an archive receive priority over others. Western institutional archives often reflect the perspective (and expectations) of the cisgender, heterosexual white man through their “policies of care for materials” (Bird 47). Bird’s culturally insensitive encounter with the CMS archive pinpoints where institutional archives are predisposed to fail marginalized groups, which simultaneously stresses the salience of grassroots methods to the study of histories disenfranchised by the ruling classes. She crucially observes how the definition of an archive shifts depending on the role one occupies or has occupied in the dominant historical narrative. Yet, instead of concluding that the definition of an archive is randomly varied, Bird determines that the very incompleteness of institutional archives is woven into the fabric of grassroots alternatives. In other words, non-institutional archives do not replicate institutional ones, but they queer the expectations of an archive to imagine the stories that never found their way into our textbooks.

At the same time, Bird admits that institutional archives can accommodate their patrons individually. During her visit to the Provincial Archives of Manitoba, the archivist accommodated her request to consult the Selkirk Treaty, an “interaction [that] supported [her] sense of claim on this historic document that represents so much for [her] community” (Bird 48). The “sense of claim” she develops as a result of the proximity to this treaty is not solely about land but knowledge—of the document itself, and how to outwork “settler colonialism in the archive” (Bird 45, 48). An incisive detail that Bird raises is that the future of an archive is not merely predicated by an untouchable past. Bird implicitly reiterates Arlette Farge’s suggestion that “an archive presupposes an archivist, a hand that collects and classifies,” and in doing so, locates what Cvetkovich misses: when someone visits an archive, they become a part of that archive, and they continue to change it even if their presence is subversive (Farge 3). Moreover, Bird assesses that the colonial histories of institutional archives do not prevent them from improving their partnerships with Indigenous communities. For example, Indigenous Knowledge Centres (IKCs) foster different forms of kin. IKCs respond to the need for an Indigenous-led community resource that accounts for the effects of settler colonial government policies, but they also exemplify how “Indigenous relational methodologies can be borne out in institutional practice” (Bird 50). By juxtaposing the possibilities of institutional archives versus IKCs—and how they can sustainably overlap—Bird judges that not all forms of access to an archive are equally valuable, yet none are worthless, either. She does not dismiss institutional archives altogether and instead emphasizes the significance of reclaiming her heritage within the institutions that disenfranchised her ancestors. IKCs embody a hybrid approach to archival research that Cvetkovich does not explicitly consider in the context of the Lesbian Herstory Archives.

While it is a mistake to directly equate modes of Indigenous relationality to those of queer relationality, Bird’s framework offers an expansive alternative to the ways that marginalized communities cultivate meaningful networks of relationality across archival spaces. Cvetkovich presses that “[l]esbian and gay history demands a radical archive of emotion in order to document intimacy, sexuality, love, and activism—all areas of experience that are difficult to chronicle through the materials of a traditional archive” (241). She does not totally negate the role of the institutional archive but insinuates that these archives lack an emotional dimension (whether they are radical or not is another issue). In her book Feeling Backwards, Heather Love states that “[w]e need a genealogy of queer affect that does not overlook the negative, shameful, and difficult feelings that have been so central to queer existence in the last century” (127). The Lesbian Herstory Archives animate a version of queer history that respects the relevance of backward feelings; however, Joan Nestle, one of the founders of the LHA, insisted that “the archives should share the political and cultural world of its people and not be located in an isolated building that continues to exist while the community dies” (Cvetkovich 250). I struggle with this idea because it implies that institutional archives are not active agents in the formation of queer history and feeling—even if it is for the worst. Whether Nestle was calling for the severance of institutional and non-institutional archives is unclear, but her reclamatory aspirations for the LHA pose a distinct risk: if the archives detach themselves from the histories of shame and repression they are grounded in, the contemporary reader will not understand how their alienation, as readers, connects them to queer subjects of the past and present. Therefore, the sense of claim with which Johannah Bird was endowed after her visit to the Provincial Archives of Manitoba elucidates the affective potential of knowledge-based institutional archives, and is a helpful guide to imagining how lesbian historiographical practices could productively evolve.

The Lesbian Herstory Archives arose from the Gay Academic Union, a group of “mostly gay women and men who worked or had been educated in the City University of New York” (Gwenwald). Of that group were Joan Nestle, Deborah Edel, Sahli Cavallaro, Julia Stanley, and Pamela Oline, all of whom founded the LHA in 1974 with the collective wish to access lesbian culture without patriarchal mediation. The archives lived inside Joan Nestle and Deborah Edel’s apartment in the Upper West Side of New York City until 1993. They later relocated the collections to a brownstone in Brooklyn that the LHA purchased with the help of “many small donations from lesbians around the country” (Cvetkovich 241). Because the building was once a house, the LHA’s informality contrasts the imposing and occasionally restrictive architecture of some institutional archives. Unlike most institutional archives, patrons do not need to request materials ahead of time and can explore the nooks and crannies of 484 14th Street at their leisure. The LHA’s spatial organization queers the expectation of an archive, but it does not guarantee its accessibility.

While Cvetkovich claims that the LHA’s administrative hurdles are inseparable from the overall experience of engaging with a lesbian archive, I am hesitant to let her theory excuse the limitations of a grassroots archive. Bird emphasizes the relevance of proximity when she consulted the Selkirk Treaty and CMS letters, saying that it “enlivened [the document’s] history for [her] and created an even greater sense of closeness to the people who marked it” (48). Factors that can impede a document’s proximity to its reader include an archive’s opening hours, its capacity to digitize holdings, and the geographic scope of its collection. The LHA’s quarters, albeit familiar, are only available to visitors (by appointment) for about two hours, 2-3 times per week. These hours change monthly, and the schedule for the following month is released in the last week of the previous month. For out-of-town visitors, this system can inhibit their contact with the archives because they can only plan so far ahead. Like many grassroots archives, the LHA does what it can with the resources at its disposal, namely limited funding and volunteer librarians, cataloguers, and staff. I raise these complications not to berate the LHA but because it demonstrates the gaps institutional archives are better positioned to fill.

With access to greater funding and resources, institutional archives can expand the breadth of their online catalogues more efficiently than their grassroots counterparts through digital reproduction, but digitizing materials is contentious for its own reasons. Bird argues that “while film and digitization can facilitate greater access to materials, they facilitate access of a certain kind” (45). The physical attributes of an archival piece are less distinguishable when “other technologies” mediate the reader’s window onto the object, but in saying this, Bird does not forsake the utility of digitized materials; instead, she maintains that “Indigenous researchers and communities should have access to the range of materials where possible” (45; 50). As an archive that seeks to “document the widest range of Lesbian experience from all geographic, cultural, political and economic backgrounds and historical contexts,” the LHA’s policy involves accepting any donation that a lesbian deems important in their life (Greenwald). These commitments simultaneously build upon and contrast each other because, as a volunteer-run archive, the speed at which they can catalogue materials—let alone digitize them—is undoubtedly impacted. The LHA has an impressive digital collection for its size, but what struck me while sifting through it was how the overwhelming majority of materials originated from New York, Boston, and San Francisco. Due to the LHA’s organizational structure, they are not adequately equipped to represent and support queer people from outside these urban centres. My rather nitpicky critique has less to do with the LHA and more to do with recognizing the prevalence of metrocentrism in queer historiography. However, it raises the question of whether the LHA’s methodology, in queering the methodologies of institutional archives, actually allows it to be as inclusive — and exhaustive — as possible.

Since its inception, the Lesbian Herstory Archives has vitally shaped and preserved records of lesbian existence in a world where sapphic feelings remain fundamentally misaligned with dominant ideology. Yet, it is reductive to assume an inherent and diametric opposition between queer history as it is and how institutional archives may choose to narrativize it. My critique of the LHA is not an effort to equate it with gay and lesbian archival collections housed in public libraries or universities but to critically examine the valid urge to overlook the weaknesses of a grassroots collective. There is a satisfying proximity to what Arlette Farge describes as the “utopian dream” of “recover[ing] a time that has been lost” in an archive that is by and for lesbians, but I argue that this proximity is compromised if users of the LHA overlook or justify potential operational issues on the primary basis that it is not an institutional archive (Farge 16). Both institutional and non-institutional archives shape our present realities, not because of the texts they house, but because the hand that holds the archive is also part of it. While the variability of the human prerogative limits an exact definition of the archive, it begs a separate question: is it better to know what archive is, or how it works?

Works Cited

Bird, Johannah. “Indigenous Relational Methodologies and Archives.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 113, no. 1, 2024, pp. 41-59, https://doi.org/10.1353/tap.2024.a925832. Accessed 15 October 2024.

Farge, Arlette. The Allure of the Archives, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013. https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.12987/9780300180213.

Gwenwald, Morgan. “Our Herstory.” Lesbian Herstory Archives, https://lesbianherstoryarchives.org/about/a-brief-history/. Accessed 14 October 2024.

“In the Archive of Lesbian Feelings.” An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures, by Ann Cvetkovich, Duke University Press, 2003, pp. 239-271, https://muse.jhu.edu/book/68580. Accessed 15 October 2024.

LGBT_History [@lgbt_history]. “A DAY WITHOUT LESBIANS IS LIKE A DAY WITHOUT SUNSHINE.” Instagram, 26 April 2017, https://www.instagram.com/lgbt_history/p/BTXKWOxF_J-/. Love, Heather. Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History. Harvard University Press, 2007.