By Michelle Siegel

Maus by Art Spiegelman and Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi engage with analeptic memoir conventions in different ways. Maus follows Art reuniting with his estranged father to recount and illustrate the latter’s experiences as a Holocaust survivor, and Persepolis sees Marjane recounting her experiences growing up in Iran during the Revolution in the 1980s. In Maus, the memories of the Holocaust, which make up the majority of the story, come from Art’s father, Vladek, rather than Art himself. Persepolis follows a more conventional structure, as Marjane writes of her own childhood, beginning with the onset of the Revolution and ending with her definitive departure from Iran. There are many tonal and narrative differences between the two, but neither is a more definitive portrayal of childhood—in fact, the variations reflect the variety and multifaceted experiences of individual histories. Although Marjane in Persepolis narrates her own historical story in a way that Art in Maus does not, both works represent childhood by selectively detailing certain historical events that they did not personally witness, imbuing literal and metaphorical childlike imagery into their illustrations, and exploring the nuances of parent-child relationships once the latter are also adults.

As a narrator, Art recounts events he did not personally witness from the lens of adulthood, subtly appeasing his childhood curiosities after growing up. In Maus, while Vladek is not unwilling to discuss his past with his son, he does so to try to maintain a relationship with Art rather than out of any moral or civic obligations. Art constantly challenges Vladek’s agency in the order and contents of his retellings, admonishing his father for his tangents and forcing him to tell a chronological, focused story. Art, as the one pushing his father to recall his personal history in a specific way, holds agency over the conception of the story in its medium. The novel’s first scene sets this up: Art’s friends abandon him after his roller skate breaks, but when he cries to Vladek about it, the latter man admonishes him for trusting friends at all, arguing that if they were locked in a room together without food for a week, those bonds would become useless (Spiegelman 5-6). This brief anecdote sets the tone for the story and Art’s commandeering of Vladek’s past, as Art feels the shadow of the Holocaust and his father’s trauma and survival instincts over his entire adolescent life. Even though he does not personally live through it, the notion of Art’s agency over Vladek’s story is complicated by the degree to which the Holocaust continues to permeate throughout their lives. Art tries to keep his recording sessions with Vladek clinical and focused on the project but repeatedly questions his father about random, specific details within his stories. In one session with Vladek, Art goes on a walk with him and asks him a few elaborating questions about his maternal family and their detainment prior to getting shipped to Auschwitz. This devolves with Vladek excitedly picking up a loose telephone wire and getting into a brief spat with Art about finding instead of paying for things before Art angrily pushes him to continue telling his story (Spiegelman 116). It also speaks to the larger dynamic between Art and Vladek; almost all conversations end up with the latter giving a neurotic, off-topic lecture. Art’s curiosity for certain details is akin to that of a child, but he cuts Vladek off whenever his tangents get off-topic and sentimental. Vladek continues to patronize and ignore his son’s agency as an adult, deepening Art’s frustration and resentment and leading him to reject Vladek’s attempts to control the dynamic of both the novel and their relationship. Art tries to force the narrative to remain focused on Vladek’s story, but his childhood trauma is clearly reflected by his angry outbursts at Vladek. He does not try to exclude his father from the narrative, but he does take command and ownership over how the story is drawn and presented in its novel form.

In Persepolis, conversely, Marjane uses the narrative to tell her own experiences rather than solely those of a family member. As she lived in Iran during the Islamic Revolution, there is a sense of morality and agency in Marjane telling her own story. As she recounts numerous moments from her adolescence, the novel more tangibly encompasses childhood nosiness and curiosity. Marjane is a particularly outspoken kid but can represent childhood through a broadly relatable experience: wanting desperately to, at minimum, get more information about random topics. Early in the narrative, Marjane mentions the destruction of the Rex Cinema, which was set on fire after the doors were externally locked—authorities did not arrive for almost an hour, ensuring the deaths of everyone in the building. She draws a portrait of the burning structure, featuring wispy ghost figures with skeletal faces, screaming in homogenous agony as they try to rise and escape from the building (Satrapi 14-15). Although she was neither inside the theater nor one of the spectators witnessing it directly, the way she learns of the incident—eavesdropping on her parents at night—indicates childhood curiosity and mischievousness. The incident is closer to Marjane and her family in a civic, localized manner, which validates its inclusion in the novel. Even though Marjane narrates Persepolis as an adult, her adolescent curiosity largely drives her understanding of events that she both witnesses and only hears about. Almost all of the novel’s imagery centres on Marjane and her family, and the frames that don’t are explicitly tied to the various constructions of Marjane’s childhood imagination. As a narrator, Marjane is closer to the story, and thus replicates her childhood and family dynamics in more direct ways.

Maus and Persepolis both incorporate imagery evocative of childhood, but the former presents them in a more literal sense while the latter uses them metaphorically. Because Persepolis follows Marjane as both a child and a young adult, different moments from her adolescence become more significant when compared to the trauma that Marjane experiences as a young adult with more life experience. When, during their childhood, Marjane’s friend and her family come over for dinner, the friend’s father recounts the torture he and others experienced in prison. Upon hearing the stories, she immediately pictures the men getting whipped, burned with irons, and chopped into pieces (Satrapi 51-52). In these descriptions, the wording of the torture is extremely gruesome and traumatic. Marjane’s images are not intentionally humorous but exude a sense of morbid wonder because of their anatomical inaccuracies. The drawings are almost macabre in depicting a dismembered man as a doll, sliced horizontally down his body and devoid of any interior organs and blood (Satrapi 52). Similarly, when Marjane writes about the burning of the Rex Theatre, she depicts the ghosts in a childlike, unrealistic manner. Their faces are evocative of Munch’s painting The Scream, with wispy bodies akin to white sheet Halloween ghost costumes (Satrapi 15). The illustrations’ imagery reflects how a child would understand and process violent and traumatic events around them. Her version of events does not downplay the horror and severity of what has happened but presents it in a manner relative to the adolescent identity of the narrator. Serious historical texts often frame children’s perspectives as unimportant or unvaluable, which Persepolis subverts by using childlike, imaginative images to represent grave events seriously. This subverts typical audience expectations of a historical memoir by legitimizing the holistic perspective of Marjane as a child—including her accounts of history in addition to her dreams and fantasies of random events. This type of imagery is brought back and modified later in the novel when Marjane returns to Iran after living in Europe for four years. She thinks that her hometown feels like a cemetery, overlaid with images of skeletal ghosts (Satrapi 251). Although the skeletal faces are almost identical to the ones she pictured as a child, their bodies are more structured and realistic, demonstrating how her knowledge and imagination have become more realistic and painful.

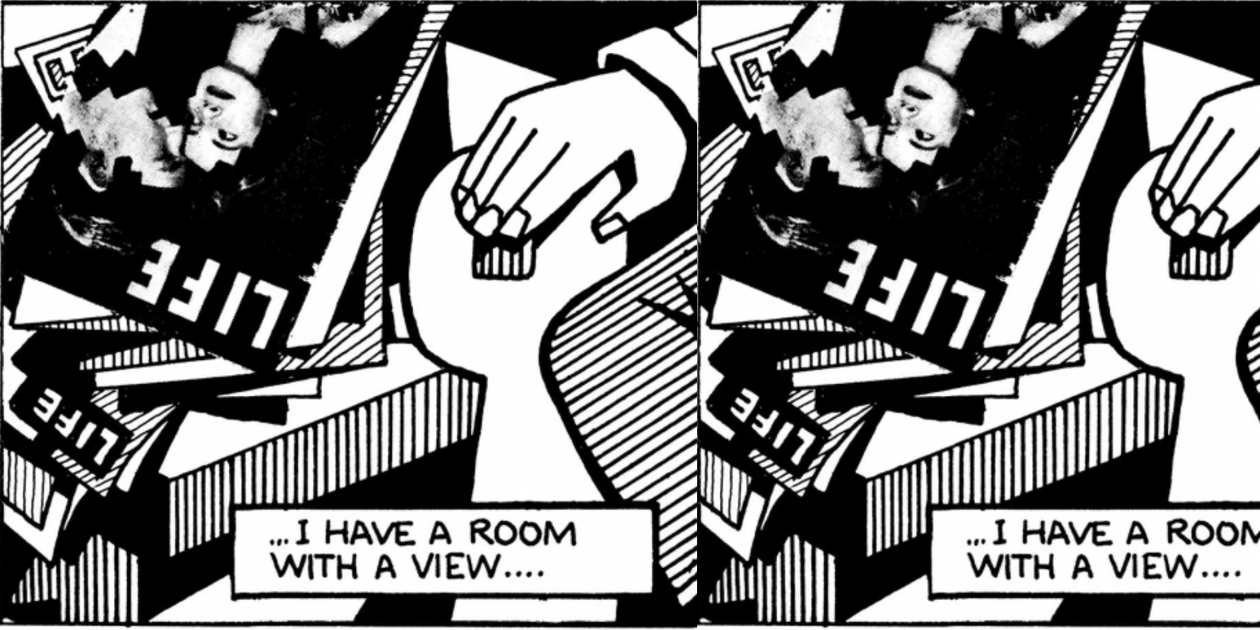

Alternatively, Maus focuses on narratives of adulthood save for its opening scene, but nevertheless highlights emotional dynamics from childhood in its imagery. Despite the visual similarities between the anthropomorphic mouse children and adults, the imagery of shrinking and scaled-down sizing emotionally characterizes them. In the second chapter of Maus’s second volume, Art is hounded by reporters and media representatives about his intentions with the novel, the implication of telling stories about the Holocaust, and the capitalistic pulls of publishing and marketing a novel: As the questions and pressure increase in each frame, Art’s figure progressively shrinks until he is the size of a child and wailing like a toddler (Spiegelman 42) A scene in which he speaks to his therapist follows this sequence, still physically aged down to child-sized, but with the emotional weight of his adult self—even at his size, he smokes a cigarette (Spiegelman 43-46). This uses more literal imagery to reflect the hold that his childhood has over Art, as the pressures of his adult life lead him to confront very mature situations from a more unchecked, youthful mentality. His childhood is a part of his adult life, which Spiegelman visually captures in Maus through the humour and irony of a child-sized anthropomorphic mouse smoking cigarettes. Because Persepolis begins with Marjane’s youthful memories and Maus follows, primarily, Vladek’s younger adulthood, they acknowledge different points of childhood from referring broadly to childhood innocence and shame, respectively.

While Persepolis demonstrates a healthier and more reciprocal familial dynamic than Spiegelman’s in Maus, both novels portray complications in parent-child relationships once the latter grows up. Although this framework stems from portrayals of adulthood, both novels establish that later relationship dynamics stem directly from childhood experiences. At the start of Maus, Art and Vladek are estranged and have not spoken in multiple years. Part of these difficulties derives from their memory of Anja, Vladek’s late wife, and Art’s mother. Maus only follows Art through the lens of his visits with his father and his illustrations of his father’s experiences in the Holocaust, and thus his relationship to Anja is only implied in certain chapters rather than explicitly addressed outside of one of Art’s comic strips (Spiegelman 100-104). Maus sees Vladek speak multiple times about his undying love for Anja; Art’s grief is silently implied through his reactions to these tangents and speeches. While the full nuances of Art and Vladek’s relationships with Anja are not specifically explored, her absence in their lives demonstrates the emotional and physical distance between father and son. A large part of Art’s resentment for Vladek, however, stems from how the latter gatekeeps Anja and her memory. At the end of Maus’s first volume, Art explodes at his father upon finding out that Vladek had burned Anja’s diaries—which detailed her feelings and experiences during the war. He calls his father a murderer, to which Vladek responds by chastising him for addressing his father that way (Spiegelman 158-159). Vladek’s response exemplifies his attempts to wield his power as a father over Art as his son. He monopolizes Anja’s memory as his wife and eliminates any chance Art has of understanding her on a more lateral, adult level outside of Vladek’s accounts. This demonstrates the ways in Maus that childhood is tied to family, as all of the novel’s allusions to Art’s past are connected to Vladek as a father.

Persepolis, on the other hand, portrays similar complications in maintaining the parent-child dynamic whilst showing a more reciprocal and positive familial connection. Marjane maintains a strong relationship with her family throughout the novel, which factors into her depression over her academic, social, and physical failures in Europe. Just before leaving to return to Iran, she smokes cigarettes in defiance of her doctor’s orders, admitting to herself that she would rather put herself in harm’s way than confront her shame for not fulfilling her parents’ goals for her. Despite carrying this sham, Marjane primarily wants to reunite with her parents (Satrapi 244-245). Similarly to Art in Maus, her feelings regarding her parents return her to a child-like emotional place in spite of her physical adulthood. Initially, she resists telling her parents about everything that had happened to her while living in Europe, almost trying to protect them from the truth as if she was their parent. When Marjane returns to her house, she instantly sees the couch where her parents told her about Austria. This memory triggers her and she immediately talks off to her bedroom to avoid thinking, let alone openly discussing her time in Europe (Satrapi 247). Unlike Art in Maus, Marjane does not resent her parents for their actions, opting to close herself off from them because of her depression and fear of having disappointed them. She eventually starts to talk about her painful time in Europe to her family, hoping to feel supported and understood by them (Satrapi 267). This desire reflects her return to the emotional role of a child, as Marjane strives to feel seen and comforted by her parents. Although the complications between Marjane and her parents are not rooted in any major fight, they still demonstrate how parent-child relationships get complicated as children grow up. Marjane is never fully emotionally estranged from her family but faces difficulties in reconciling her adult status with her longstanding childhood yearning. The dissonance between the family is heartbreaking but not irreconcilable, as all of Marjane’s family are relatively in touch with their feelings and their situation. Such efforts for reconciliation, however, are not feasible in Maus, as Art is too unwilling to reconnect with Vladek and only acknowledges his childhood mentality when externally forced back into it.

Although Maus more sparingly uses literal images to depict the overwhelming influence of childhood, it mirrors similar nuances in Persepolis, which uses a more conventional structure to portray childhood. Maus portrays a more fraught familial relationship between Art and Vladek, ultimately presenting childhood as a place of pain that adults, years later, cannot entirely escape. Marjane does not glamourize her childhood in Persepolis but expresses a yearning for it when she returns to Iran and is unable to reconcile her memories of her past, with whom she becomes years later. The two novels’ protagonists portray their childhoods and parental relations differently, but both do so through narrative framing and detailed illustrations. While Persepolis can explore childhood through Marjane’s eyes, Spiegelman’s more indirect representations of childhood in Maus are not less powerful because of it. By taking different paths to portray different childhoods, both graphic novels build towards a broader, more holistic understanding of the ways childhood can impact adults.

Works Cited

Satrapi, Marjane. The Complete Persepolis. Pantheon Books, 2004.

Spiegelman, Art. Maus I. Pantheon Books, 1986.

—. Spiegelman, Art. Maus II. Pantheon Books, 1991.

About the Author: Michelle is a fourth-year student at McGill, majoring in English Literature and minoring in Communications and Classics, and works as an Arts & Entertainment Editor at the McGill Tribune. She likes critically analyzing reality television, deconstructing the lens of nostalgia, and incorporating puns and word play into as many writing pieces as possible.