by Emma Williamson

The Malleus Maleficarum, written in 1487 by German churchman and inquisitor Heinrich Kramer, is one of the European witch craze’s most infamous books and occupies a vital place within the history of sexuality (Garrett 32). Primarily a manual for identifying, prosecuting, and exterminating witches, it played a significant role in the witch trials that swept across Europe during the late medieval and early modern periods. The book’s three parts discuss evidence of specifically female witches, the legal procedures for identifying and punishing witchcraft, and, most prominently, the deplorable actions and sexual crimes of witches. Previously, neither heresy nor sorcery had been an exclusively female accusation (Honegger 796). The text’s intensely misogynistic position supplants previous theories positing witchcraft as a crime affecting both sexes and inscribes witchcraft as a primarily female, and primarily sexual, crime (Smith 87). By salaciously detailing witches copulating with incubus demons, encouraging abortions, instigating sterility and castration, and manipulating sexual relations between husbands and wives, Kramer magnifies the threat witchcraft and women’s sexual activity pose to Christian society (Roper 122). Citing biblical, medical, classical, and medieval texts to corroborate his claims, Kramer imbeds these deviant actions within the early modern legal framework “which claims sex in order to regulate it,” developing a mode of witchcraft discourse which inscribes a new kind of fear, discrimination, and heresy onto female sexuality (Garrett 33). Witness “testimony” of magical castration, orgasmic sex with demons, seed stealing, and old women luring young virgins, all function as exempla to corroborate the Malleus Maleficarum’s tirade against witchcraft and women. However, these stories also highlight deeper anxieties about women’s sexuality and suggest that female bodies are innately deviant and perverted. Malleus Maleficarum thus not only invokes a gendered, feminine conception of witchcraft, but suggests that women’s bodies and the sexual deviancy of witchcraft are inherently tied. In doing so, Malleus presents a deadly opposition between the sexes and posits that it is only under the staunch policing of women’s sexuality that they do not turn to the corruptions of the Devil.

Kramer begins his treatise by weaponizing biblical texts to highlight women’s susceptibility to witchcraft and connects women to an innate weakness and carnality seen since the original sin. Interrogating why the “condition of women” leads them to “subordinate themselves to demons” and undertake “such filthy acts” such as sex with evil spirits, Malleus cites the biblical precedence of women’s innately flawed condition (Kramer 159–160). He explains:

There is a natural explanation, namely that she is more carnal than a man, as is clear in connection with many filthy carnal acts. These defects can also be noticed in the original shaping of woman, since she was formed from a curved rib, that is, from the rib of the chest that is twisted and contrary, so to speak, to man. (Kramer 165)

Linking the seductive and lustful nature of witches to the erotic, “carnal” nature of the first woman suggests that women have suffered deformity and, therefore, susceptibility to defective behaviour since the beginning. This gendered conception of “natural” defects shifts the concern of witchcraft and its sexual temptations as something faced by “persons of both sexes, to a heightened scrutiny of women’s sexuality as unavoidably bound to the demonic through its excess” (Garrett 34). As Kramer ties women’s sexuality to the demonic, with her “connection to many filthy carnal acts,” he sets a dangerous precedent for the rest of the treatise that implies any expression of women’s sexuality, if not strictly policed within male power structures, is inherently evil. Kramer manipulates the Biblical story of Genesis to present physical “shaping” as confirmation of female proclivity for apostasy. Stating “Woman, therefore, is evil as a result of nature because she doubts more quickly in the Faith,” Kramer asserts it is women’s very nature to become evil, and there is seemingly no way to avert such biologically innate calamities (166).

This description of female “shaping,” existing “twisted and contrary” to man, also creates a theory of gender that situates men as the voice of reason and control over women and their “carnal” defects (Kramer 165). Men, due to their “intelligence, [are less likely] to commit the renunciation of the Faith” and act on the bodily impulses of witchcraft (167). While in women, “everything is governed by carnal lusting, which is insatiable in them” (171). Equating women with “sexuality, matter, nature which had to be dominated by man, who defined himself as the only pillar of reason and judgement” further separates male nature from the wickedness of witchcraft and promotes women as the instigators of bodily lust and sin (Honegger 797). This stigmatizes women as solely fleshly, unthinking, and “a perpetual threat to the holy project of male sexual discipline” (Garrett 34). Women “do not know how to maintain a middle course in terms of goodness or evil… when they pass over the boundaries of their condition” (Kramer 160). This further promotes the binary gender notion that men are associated with judgement and the mind while women and their lust are only associated with the body. In conjunction with humoral theory, this suggests that the wet and cold porosity of women to their environment forces their humors to flow in and out with no ability to self-regulate without the control of a man. By creating a disparate opposition of the sexes, Malleus promotes the vilification of women as witches not only because of their actions but simply because of the evil biologically inscribed in their nature.

Malleus explores the sexual function and pleasure of women’s genitals by foregrounding their corruptibility and ties to the demonic. Although Kramer states “the power of the demon is in the loins of humans,” he dramatically privileges women’s genitals “as the bodily site most vulnerable to demonic influence” (128; Garrett 38). Explaining how women have sex with demons, he describes:

Although the incubus demon always works visibly from the point of view of the sorceress … in terms of the bystanders it is frequently the case that the sorceresses were seen lying on their backs in fields or woods, naked above the navel and gesticulating with their forearms and thighs. They keep their limbs in an arrangement suitable for that filthy act, while the incubus demons work with them (Kramer 313)

This scene all but declares that the woman is masturbating alone. To account for the forbidden nature of a woman’s solitary sexual experience, however, Kramer reframes the act within a demonological lens (Garrett 41). Witchcraft prosecutions were “related to attempts to take away women’s control of their sexual and reproductive lives” (Barstow 8). Kramer, in describing this scene as a “filthy act” of the demonic, thus stands for the vilification and denial of women’s autonomy over their own sexual pleasure. Codifying autoeroticism with the demonic also presents women’s sexual self-pleasuring not only as something that does not exist (for if it appears that way, there is an invisible demon involved), but also as something inherently evil. A woman acting on sexual urges, even if she appears to be alone, is coupling with the demonic and acting out of sexual deviancy. To Kramer, a woman alone touching her genitals is evil, and he constructs a narrative of invisible incubuses to ratify his claims.

The imagery of this scene depicts a salacious account of a woman “gesticulating” in sexual pleasure. The broader text, however, denies the assertion that she is acting out of active masturbatory gratification as it reminds the reader that the witch is in a submissive position to the demon. “Lying on her back” with her “limbs in a suitable arrangement,” the woman is passive to the demon’s actions. Demonic sexual coupling, Kramer emphasizes, comes at the cost of women “subordinating themselves to incubus demons” (83). Even in pacts with the Devil, women are not free of patriarchal control and dominating male forces. Therefore, despite her apparent sexual pleasure, the male reader is comforted in knowing that she is not acting autonomously in masturbatory pleasure but coupling with a demon against her will. While describing a woman’s attempt to circumvent men while experiencing sexual pleasure, Kramer suggests that such autoeroticism is only possible with the help of the Devil, another male force.

Malleus further engages with women’s eroticism as it discusses the reprehensible idea of women desiring sex for pleasure. Kramer later reflects on the sex between witches and demons, claiming women are “no longer subordinating themselves to a wretched form of slavery against their will… but doing so of their own accord for physical pleasure (a most foul thing)” (308). Women engaging in any sexual acts for nonprocreative purposes was a monstrous, “most foul thing” in the European early modern period. Nonprocreative sex was seen as a “travesty to the Christian institution of marriage” (Borris 26). In the Catholic analysis of sexual morality, “even heteroerotic vaginal coitus between married partners was seriously sinful, if too motivated by desire for pleasure rather than for procreation” ( 28). Within these social structures, as Kramer emphasizes women’s desire “for physical pleasure” or any form of sex without procreation, he conflates these desires with the demonic. This both vilifies women’s sexual pleasure and suggests that any woman with the desire for sex, without the desire for pregnancy, is sexually deviant.

As pleasure was “sinful,” the idea of women achieving orgasm with demons was doubly troubling because of its potentiality for impregnation with demonic children. The Canon of Medicine (1010) highlights the importance of female orgasm in the process of impregnation: “when no [female] sperm is emitted, there is no child” (Borris 130). Malleus cites the importance of female “seed” as it explains “through the debauchery of the flesh… in the loins of men, since the seed is emitted from there, and it comes from the navel in women” (Kramer 126). The acknowledgement of the existence of female “seed,” and the emphasis on sinful demonic sex as a “physical pleasure” for women promotes a dual-pronged anxiety for male readers. Women were medically considered “slow to emit sperm, and their desire remains unsatisfied, and for this reason, there is no pregnancy” (Borris 130). If men were incapable of pleasuring their wives to orgasm and thus anxious at the premise of failing to release female “seed,” the idea of their wife achieving orgasm and absolute “physical pleasure” with a demon is doubly problematic (Kramer 308). Women’s sexual pleasure at the hands of demons, therefore, encourages male cuckold anxiety. It destabilizes structures of sexual control while also leading to anxiety over progeniture and the potentially illegitimate familial lines. This vilifies women’s non-procreative sex, especially that which involves orgasm and the release of “seed,” as something demonic and encourages the policing of all aspects of women’s sexual pleasure and orgasm.

Female sexuality is further indicted of corruption as Kramer continues to promote progeny-based cuckold anxiety in his male readers when he explains: “we cannot altogether deny that when a married sorceress is impregnated by her husband, the incubus demon can taint the conception through mixing in another man’s seed” (311). Control or tampering with any aspects “of reproduction could have been viewed as an abuse of power, and meddling in such affairs may have been considered blasphemous” to early modern readers (Spoto 59). The “blasphemous” idea that demons can mix male seed, or even “accost [a woman] with [another man’s seed] in order to taint the progeny,” highlights male fears of virility and fear over their own reproductive abilities (Kramer 109). While these demonic dialogues leave male readers anxious over “sorcery committed against the power to procreate,” they also associate women’s sexual promiscuity with witchcraft and the demonic (181). Emphasizing “carnal lusting” as “insatiable” in women while concurrently suggesting women, through witchcraft, can become impregnated by the seed of men other than their husbands, Kramer ties any form of female sexual promiscuity to the demonic (171). Affairs, to Kramer, is demonic deviancy. Extramarital sexual promiscuity with multiple partners lies beyond the bounds of traditional female societal sexual constraints. Just as he associates masturbation with the demonic for being an autonomous female pleasure beyond the bounds of prescribed social norms, so too are women with multiple sexual partners. The seed-mixing anecdote highlights the potential women’s sexuality has to invert the patriarchal power dynamics while also pulling on male anxieties surrounding virility and impotence. By arguing “seed mixing” can “taint progeny,” Kramer gives men an out to blame their own impotence on women’s deviancy and supposed infidelity (311). Women holding the power to sexually transgress with multiple partners and potentially affect reproduction oppose the patriarchal social order. As Kramer accuses women of the potential to taint progeny through witchcraft, he also calls to decry any sexuality women express outside of a husband’s reproductive desires as witchcraft.

The paranoia of witches inverting the patriarchal power dynamic also manifests itself in a testimony describing witches collecting local men’s penises. Kramer describes:

Sorceresses who sometimes keep large numbers of these members (twenty or thirty at once) in a bird’s nest or in some cabinet, where the members move as if alive…these things are carried out through the Devil’s working and illusion… A certain man reported that when he had lost his member [he had] gone to a certain sorceress to regain his well-being. (Kramer 328)

The removal of the male sex organ in the hands of the witch not only impedes “the procreative force… taking away the limbs appropriate for this action,” but also suggests a loss of phallus-derived male sexual power (Kramer 171). The literal and metaphorical emasculation of losing one’s penis to a witch demonstrates “that many anxieties surrounding gender hierarchy were related to sexual power and sexual surrender” (Smith 58). While to Kramer, women’s genitals are the height of demonic intrusion, men’s “members” are at the mercy of these women and their deviant desires. Playing on castration anxiety, Kramer advocates for active phallus assertion of the male patriarchal force. In this hyperbolic “illusion” of the “Devil’s working,” he presents the necessity of “punish[ing] sorceresses as renouncers of the Faith,” before they take the phallus of power for themselves and subvert the power structures for their own deviant desires (Kramer 480). The sexual “giving and taking of power” to Kramer is tied up in the castration of men in communities overrun with uncontrolled women and subsequently, witches (Smith 94). As they collect more penises, they sever more power from the male body and insert that power into the deviant female body. This also suggests that the nest of penises can act as a grouping of dildos, thus encouraging further carnal female sexual pleasure severed both from the male body and reproduction. The nest of penises serves as a metaphor for pure autonomous female sexual deviancy, while men are left powerless for not controlling women sooner.

Women’s bodies in Malleus are susceptible to sexual deviancy and witchcraft through Eve’s original deformity; however, they are also inherently tied to sexual corruption through the process of aging. Kramer claims that “old women can bring the effects of sorcery about without the work of demons” (113). The social tension of older, poor, widowed women relying on community support while existing outside of normative patriarchal conditions of the early modern period makes “old women” an “unassimilable social group” (Barstow 14). Due to their frequent maternal proximity to youth and their “unassimilable” existence, Kramer argues their souls are “strongly impelled in the direction of evil, as happens to old women in particular, the sight of her is rendered poisonous and harmful in this manner, especially for children who have tender bodies and are easily receptive” (113). The “poisonous and harmful” nature of their “evil,” “especially for children,” suggests the “social order felt threatened by nonconformist women, felt that church and family, and even the state, were threatened” (Barstow 15). Kramer fears the “evil” of these women is far too dangerous for the “easily receptive” minds of children, and especially little girls, who will follow the hag down the path of deviancy. Not only is the existing social order threatened by these old women, but as Kramer claims that they are most harmful to children, he also suggests that there is a “deep fear of sexually experienced, sexually independent women” (Spoto 58). This connotes a suggestion that old, “sexually experienced” women can corrupt the chastity of young women by introducing young girls to the potential sexual deviancy of their own bodies.

Multiple testimonies in Malleus cite being “led astray like this by an old woman, her companion was [also] led astray [by an old woman] in a different way” (Kramer 278). While evolving from a girl to a woman can be considered a sexual (and thereby demonic) awakening, being “led astray” by old sorceresses at the margins of society can expedite the process. Kramer notes that “the Devil’s intent and appetite are greater in tempting the good than the evil… he makes greater efforts to lead astray all the holiest virgins and girls.” Therefore, “unassimilable” old women capable of sorcery without “the work of demons,” can efficiently support the Devil in his endeavours by targeting and entrapping these “holiest virgins” with their tempting deviancy, leading them from the path of social and patriarchal purity. The potentiality of old women to tempt young women into the path of deviancy further presents his view that women’s bodies are inherently tied to the demonic, even if they are chaste up until the point of being “led astray” (Kramer 277). As he vilifies old women and highlights little girls’ vulnerability, Kramer further reiterates women’s bodies as a site of sexual deviancy and the need to staunchly police all ages and stages of women.

As Kramer targets old women for their machinations against vulnerable children and chaste girls, he also claims that the dangers of these old women stem from their “loose tongues [that they] can hardly conceal from their female companions the things that they know through evil art.” Unable to stop their “loose tongues” from telling their “female companions” about their sorcery with the Devil, Kramer presents any closed female network as one to be feared and targeted for compounding the presence of witchcraft. As he warns that these groupings of “female companions” exchange the “evil art” of demonic knowledge, he ascribes women’s groups as inherently susceptible to evil (Kramer 164). When a witch is apprehended, he advises “Concerning simple heresy, sentence her to be burned, especially because of the increased number of witnesses” (597). In fearing “female companions” or networks of women, Kramer fears witchcraft’s “sexual contagion” among unsupervised women without male policing (Garrett 41). Sexually experienced women are capable of exposing their “loose tongues” to naive young “companions,” not only exposing them to the “evil art” of witchcraft, but also the innate sexual deviancy he purports is already within their bodies. As Malleus perpetually emphasizes the vulnerability of women’s genitals to the corruption of demons, Kramer also suggests groups of women, especially old women, perpetuate the deviancy of witchcraft and its sexual crimes if they are left alone and unpoliced to go about these temptations. By warning: “Witches are not individuals, but rather a collective force of evil that must be eradicated from society,” Kramer asserts that any closed group of women is a “force of evil,” capable of the inherent capacity for witchcraft (412). One woman at a time, Kramer urges his readers to ensure witches, or any woman susceptible to “evil art,” be “eradicated.”

Malleus Maleficarum, “long regarded as one of the most influential witch-hunting handbooks of the era,” served critical functions for the “development of sexual knowledge,” and by extension, sexual paranoia and violent gender discrimination (Schuyler 37). The text’s explicit strain of discourse surrounding the female sexual body and the “nature of erotic experiences” argues that there is an innate perversion within women’s sexuality, and their ties to witchcraft have been with them since the failings of the first mother, Eve (Garrett 34). By highlighting women’s vulnerability to sexual corruption and demonic deviancy through various sexual activities and closed feminine discourse, Kramer reinforces oppositions between the sexes and women’s innate incapacity to control themselves, as well as the necessity for male control. By invoking a gendered, feminine, sexual conception of witchcraft, Malleus Maleficarum assisted in more than 200,000 executions in Europe, “the majority of them uneducated and frightened women” (Schuyler 25). The text fostered stigma around women’s sexual pleasure for centuries to come and made the accusation of “witch” an exclusively female one.

Works Cited

Barstow, Anne Llewellyn. “On Studying Witchcraft as Women’s History: A Historiography of the European Witch Persecutions.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, vol. 4, no. 2, 1988 pp. 7–19. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25002078.

Borris, Kenneth. Same-Sex Desire in the English Renaissance: A Sourcebook of Texts, 1470- 1650. Routledge, 2004.

Garrett, Julia M. “Witchcraft and Sexual Knowledge in Early Modern England.” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies, vol. 13, no. 1, 2013, pp. 32–72. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43857912.

Honegger, Claudia. “Comment on Garrett’s ‘Women and Witches.’” Signs, vol. 4, no. 4, 1979, pp. 792–98. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173379.

Mackay, Christopher S..The Hammer of Witches: A Complete Translation of the Malleus Maleficarum, Cambridge University Press, 2009. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mcgill/detail.action?docID=442875.

Roper, Lyndal. “Witchcraft and the Western Imagination.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 16, 2006, pp. 117–41. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25593863.

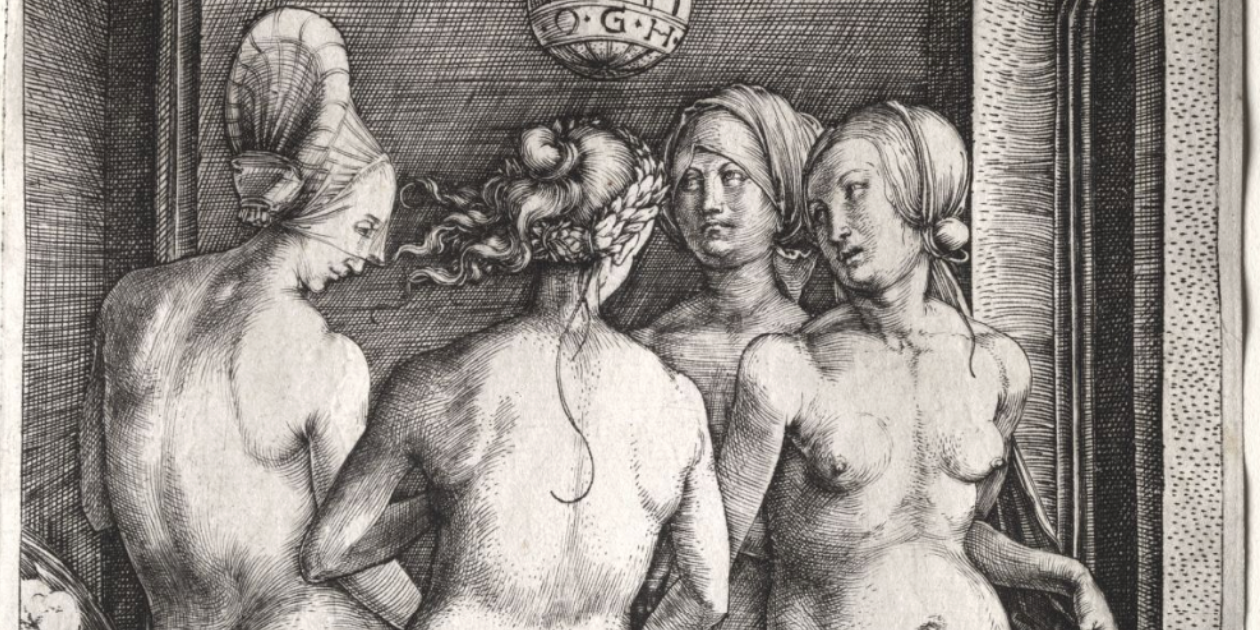

Schuyler, Jane. “The ‘Malleus Maleficarum and Baldung’s ‘Witches’ Sabbath.’” Source: Notes in the History of Art, vol. 6, no. 3, 1987, pp. 20–26. JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23202318.

Smith, Moira. “The Flying Phallus and the Laughing Inquisitor: Penis Theft in the ‘Malleus Maleficarum.’” Journal of Folklore Research, vol. 39, no. 1, 2002, pp. 85–117. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3814832.

Spoto, Stephanie Irene. “Jacobean Witchcraft and Feminine Power.” Pacific Coast Philology, vol. 45, 2010, pp. 53–70. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41413521.