TW: This essay contains references to violence throughout and a brief mention of SA in the author’s analysis of power and violence in Titus Andronicus.

Comments closedCategory: Uncategorized

His argument presents an antinomy that reveals the contingency behind the process of meaning-making: Socrates’ wisdom is a ‘nothing,’ as it were, in so far as he claims to not know anything; however, by being conscious of this non-wisdom, his comprehension of this fact becomes a form of knowledge that he can possess.

By way of synthesis, I argue that memories of colonial trauma haunt the domestic spaces of Jane Eyre and subsequently disrupt the linear trajectory of Britain’s national history. As such, a central predicament of the novel revolves around the means to purge both its characters and their dwellings of the racialized other to restore a pure and untainted British past in order to transition into an untroubled future.

Comments closedThe circumstances in which Malory invokes “the Freynshe booke” are varied, but they each operate in one of three distinguishable yet interrelated ways: marking especially notable events and actions as (un)certain, validating conflicted or ambiguous emotional responses, and calling attention to the act of recording or producing truth.

Comments closedBy tracking this evolution of the tongue from an idiom to a personal organ, one sees a parallel progression of the genre’s characters: whereas earlier speakers of autobiographical slave narratives served editor-mediated, abolitionist motives, later contemporary writers reformed the genre by depicting fully fleshed, self-governing individuals.

Comments closedThough Philip, like Derrida, treats language—specifically the financial and legal language associated with the court cases around the Zong massacre—as an entity that neutralises the violence of the Zong massacre, I nevertheless invoke Derrida, since his focus is on language as such as a metaphysics of presence that will always fail to capture force, which is, in some ways, a broader claim than Philip’s

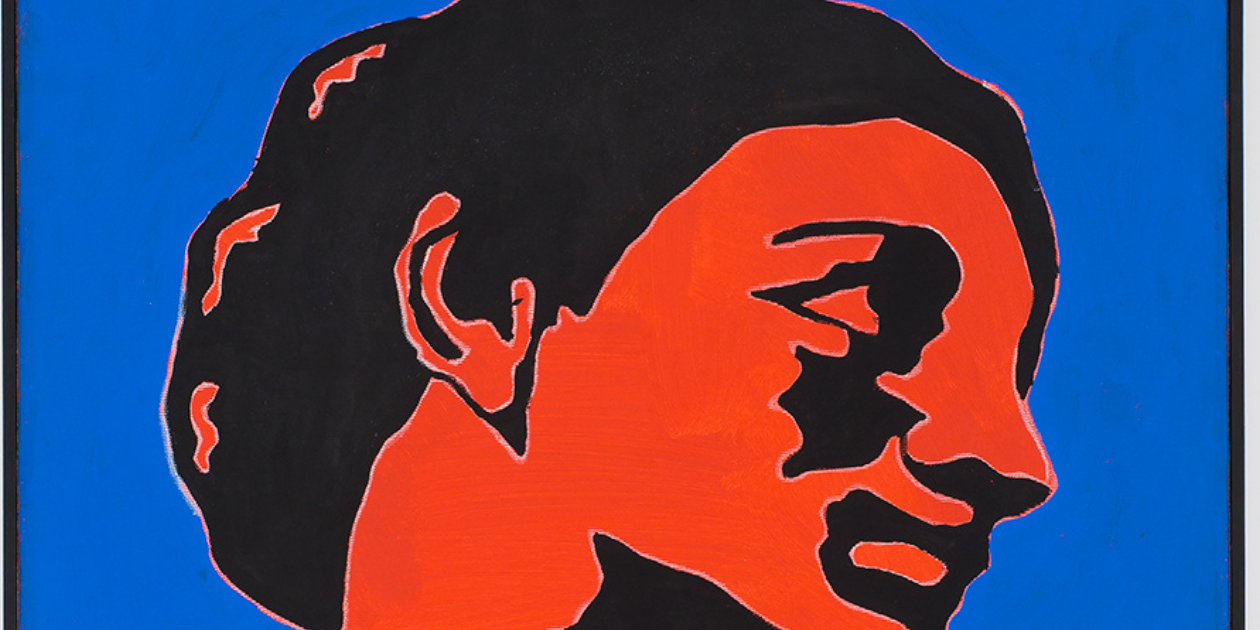

Comments closedPushkin juxtaposes literary ideals in Eugene Onegin to defamiliarize the notion of a comprehensive ethical system. In doing so, Pushkin illuminates a space between broken ideals that is entirely sympathetic to heroes and villains alike.

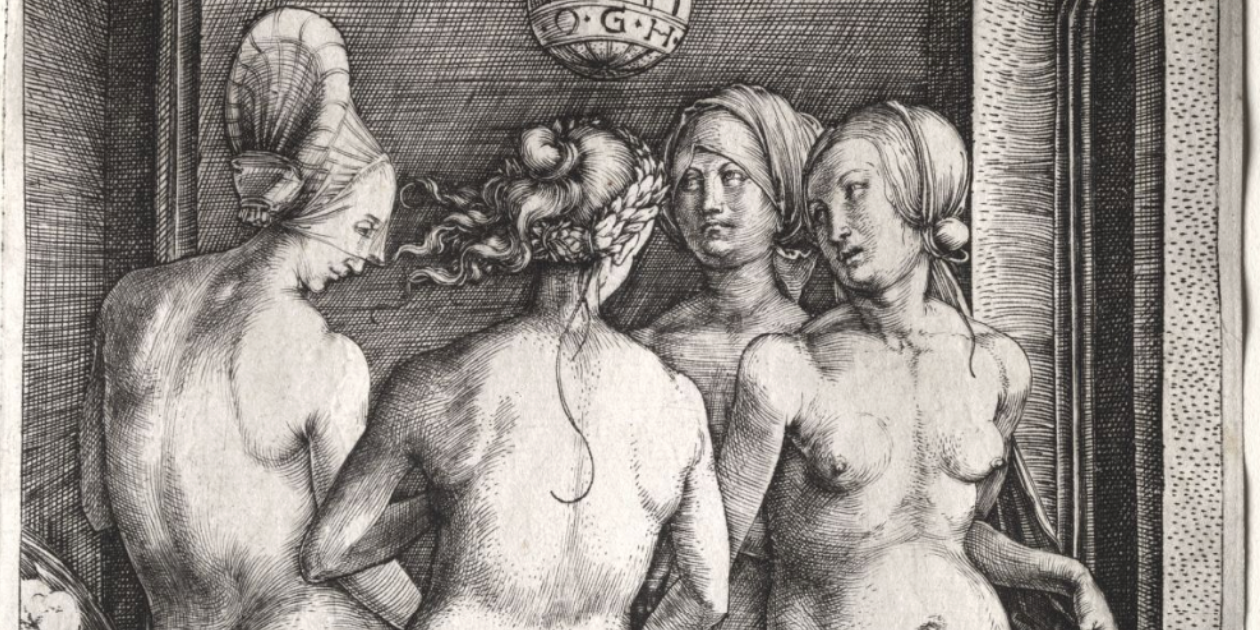

Comments closedMalleus Maleficarum not only invokes a gendered, feminine conception of witchcraft, but suggests that women’s bodies and the sexual deviancy of witchcraft are inherently tied.

Comments closedThe theorisation laid out in “World Literature and World Legislation will be the focus of my argument, and perhaps the issues that I will take with this approach might be perceptible already—or perhaps not. In any case, a theoretical exposition—something of a detour—will be necessary to sufficiently ground my argument.

Comments closed